A limited edition published to commemorate the poet’s death in April 1917 and designed to emulate the fine press editions of the early 20th century. In series with Selected Poems Rupert Brooke and Selected Poems Wilfred Owen.

Illustrated by Ed Kluz

Introduced by Jon Stallworthy

Limited to 1,750 hand-numbered copies

A limited edition published to commemorate the poet’s death in April 1915 and designed to emulate the fine press editions of the early 20th century. In series with Selected Poems Edward Thomas and Selected Poems Wilfred Owen.

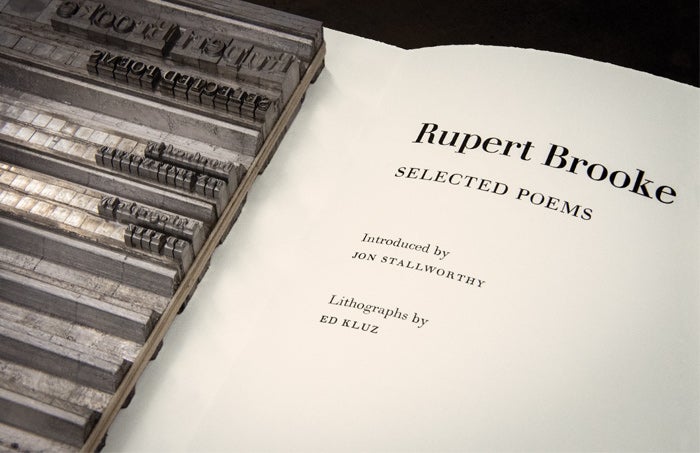

A selection of Rupert Brooke’s most famous poems presented in a special limited edition to mark the centenary of his death. The book has been designed to reflect the values of the fine press movement of the early 20th century. The text, printed letterpress, is illustrated with original lithographs and quarter-bound in leather with hand-made paste-paper sides by Victoria Hall.

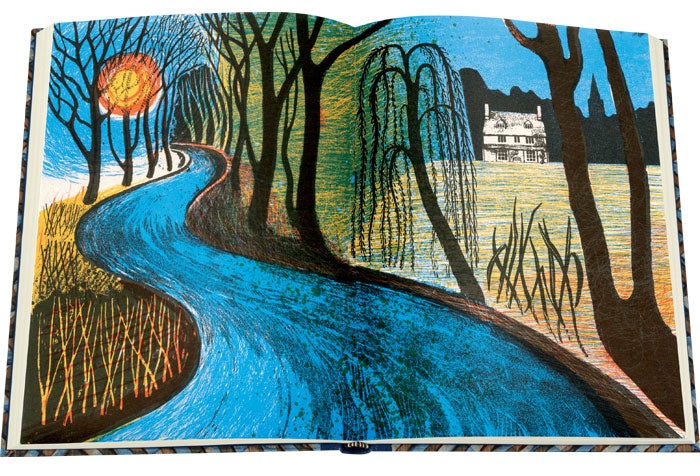

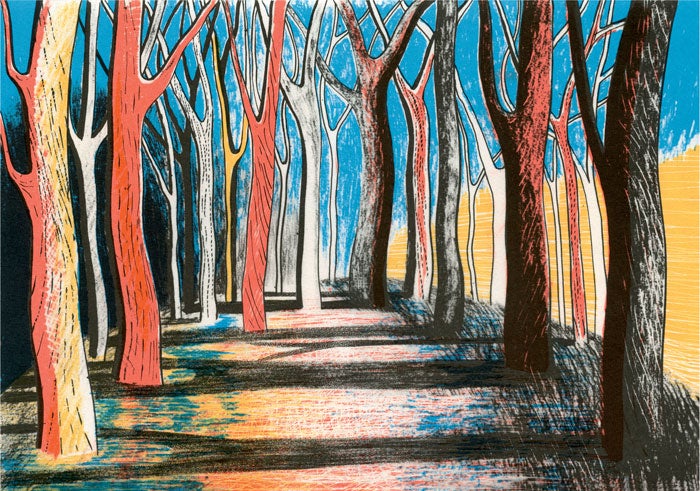

Brooke is famous both for his evocation of Edwardian England in poems such as ‘The Old Vicarage, Grantchester’ and for the wide-eyed patriotism of his later poems that herald the coming conflict. He died aged 27, before this illusion of a just and heroic war was completely shattered, although his final poem suggests that he may have begun to reconsider his idealistic stance. This edition contains superb new lithographs by Ed Kluz that capture the vitality and beauty of his verse.

Limited to 1,750 hand-numbered copies

Quarter-bound in goatskin, with paste-paper sides

Set in hot metal in Monotype Walbaum

88 pages

9 lithographs and 6 vignettes

Paper-covered slipcase blocked in gold on one side and inset with a lithograph label

Coloured top edge

9¾˝ x 7˝

His work was revered by literary greats such as T. S. Eliot, Henry James and D. H. Lawrence; W. B. Yeats called him ‘the handsomest man in England’; Winston Churchill eulogised him in a three-page Times obituary; others knew him as a tormented lover. Few literary figures have been mythologised as much as the poet Rupert Brooke.

Brooke was born in Rugby, England, in 1887. He studied at King’s College, Cambridge, living for a time in the village of Grantchester. Here he adopted a neo-Pagan lifestyle which later inspired the nostalgia of his most famous poem, ‘The Old Vicarage, Grantchester’. In 1912, at the end of a tempestuous love affair with Ka Cox, he suffered a breakdown, but found happiness in Tahiti, where he lived for several months and produced some of his best poetry. Under the patronage of his university friend Eddy Marsh he came to know Winston Churchill, George Bernard Shaw and other figures of the political and literary elite. Brooke joined the Royal Naval Division when war broke out. In February 1915, bound for Gallipoli, he developed septicaemia from a mosquito bite and died on 23 April, on a hospital ship off the Greek island of Skyros.

The Old Vicarage, Grantchester

Oh, is the water sweet and cool,

Gentle and brown, above the pool?

And laughs the immortal river still

Under the mill, under the mill?

Say, is there Beauty yet to find?

And Certainty? and Quiet kind?

Deep meadows yet, for to forget

The lies, and truths, and pain? . . . oh! yet

Stands the Church clock at ten to three?

And is there honey still for tea?

Like so many others of his time, Rupert Brooke did not live to reach his full potential, but his haunting, often prescient poems testify to his dazzling command of words and the depth of his imagination.

Brooke often mused on the certainty of death, but he also treasured deeply the vital pleasures of life — friendship and love, the ‘link’d beauty of bodies’, the joy of hearts ‘swift to mirth’. His musical poems pay homage to the quiddity of things — ‘wet roofs, beneath the lamp-light’, ‘white plates and cups’, ‘live hair that is/Shining and free’ — urging us to remember him as one who loved all that the world offered to his senses and his mind. But even while he cherishes the sensations of being alive, in his early work he evokes the possibility of a superior, ethereal form of being, free from the shortfalls of earthly emotions. Like elegies from which the sadness has been lifted, ‘The Treasure’ and the strongly Platonic ‘Tiare Tahiti’ gently insist that the fleeting moments that have made up his life, and those of his lover, will live on in ‘some golden space’.

This embracement of life and the afterlife has given us some of the most memorable verse of the Georgian school. It was a stance Brooke maintained in his group of sonnets, written while he was on leave from the Royal Naval Division at Christmas 1914. In these he anticipates that the destruction wrought by war will give way to the renewal and rejuvenation of a ‘world grown old and cold and weary’. ‘The Soldier’, famously read aloud by the Dean of St Paul’s at the Easter Sunday Service in April 1915, reassures us that in the event of his death, his essence will live on, ‘all evil shed away’, as a ‘pulse in the eternal mind’.

But Brooke’s appeal also lies in his ability to temper these beautifully rendered visualisations of destiny, death and the afterlife with a playful irony, sometimes in the form of satirical counterpoints to his own grand themes and paeans to Platonism and Christianity. Indeed, he increasingly rejected the notion of a heaven, and in his final, deeply moving poem, ‘Fragment’, found in the notebook he was using in the weeks before his death, the exuberant tone of his earlier verse is replaced by a deeply reflective awareness of the fate of his generation. Notions of honour, patriotism and a sublime hereafter give way to that of casual destruction. As many have conjectured, this last poem suggests that Brooke, had he lived longer, would likely have equalled Owen and Sassoon in his responses to the horrors of the war. At least, as Jon Stallworthy writes in his introduction to this edition, Brooke’s avowal that his heart would give ‘somewhere back the thoughts by England given’ turned out to be true; however short his life, his meditations remain alive for us today.

Hand-patterned paste papers have been used as a durable covering material for books and other objects for centuries. The sheets are first dampened and left a short while to rest. Each damp paper is then brushed all over with a coloured starch paste prepared by cooking a combination of flours, before being tooled with a handmade metal comb. The papers are vulnerable at this stage and are put aside to air-dry slowly over several hours. They are then pressed before being patterned again. After further drying, they are flattened with a big cast-iron standing press.

My early trial designs for this book featured flowing pastoral elements in pastel colours, followed by an exploration of the blues and yellows of the coast. Somehow the layered design needed something more subdued and earthy, so the final colour scheme features horizontal bands of undulating blue suggesting water or sky, with vertical bands in a colour which reflects dirt, trees and the colours of mud. Using only two colours, I have tried to create a pattern design which is complex, open and endless.

Victoria Hall began making decorated papers professionally in the late 1980s, having obtained a degree in the History of Art & Architecture from the University of East Anglia. Her work has appeared in many fine press editions, and can also be found in private and public collections including The Royal Library, Den Haag; Newberry Library, Chicago; and the Schmoller Collection at Manchester Metropolitan University.

Letterpress is the text-printing method most respected by book collectors. It can be an unforgiving medium, but in the hands of an experienced printer the results surpass anything that other printing methods can achieve. Much is written about the revival of letterpress, but Stan Lane, who set and printed the type for this edition, is not part of any revival; rather he embodies the living tradition of the craft. He was trained in letterpress nearly 60 years ago and has never used any other process. Stan has printed this book on Zerkall paper, which has a classic look and feel redolent of an era of excellence in craftsmanship. Even the smell of the ink has the distinctive quality appreciated by those who love fine books.

Illustrating the work of a poet always presents a challenge. Taking on board the ideas and imagery of a writer goes, to a certain extent, against the independent creative process of the artist. In this sense the illustrator of poetry is a conduit for the visions of others.

In order to find an approach to these illustrations, I looked for common metaphors within Brooke’s writing — water, darkness, light, solitude and the passing of time infuse the images. The second challenge was somehow to create a sense of narrative and movement within a single static representation; an image which is immediate but which also reveals itself slowly, presenting details and leading the eye, emulating the experience of reading a poem. Of all literary forms, poetry, in some ways, is most like an image. In this sense an accompanying illustration should at once work in tandem with the poem and function as an independent entity.

The challenges and rewards of autolithography

When presented with a new image-making process, I enjoy the experience of getting to know the character of the materials and finding an approach which makes best use of its particular qualities. The seemingly infinite possibilities of ink being pressed, transferred, lifted or squeezed onto paper never ceases to amaze me. The greatest challenge presented by autolithography was in translating the hand-drawn marks into the printed result. As with any print-making medium, there is the moment when the process takes control and creates something entirely unexpected. This is part of the joy of printmaking. Under the guidance of my old art school friend, Andrew Curtis at the Curwen Studio, we refined the drawings over several proofing stages. This was the most nail-biting and time-consuming part of the process, but in many ways also the most exciting.

The craft techniques employed in this edition, limited to only 1,750 hand-numbered copies, are all characteristic of those used in fine press books in the early 20th century. Published to commemorate the death of Rupert Brooke on 23 April 1915, this is the first book in our series of war poets and precedes the Selected Poems of Edward Thomas and of Wilfred Owen.

This edition is slipcased in Forest Stewardship Council certified, felt-marked, indigo Freelife Merida paper inset with a detail from the lithograph created to accompany ‘The Old Vicarage, Grantchester’ and blocked in gold with the name and dates of the poet; Rupert Brooke, 3 August 1887, Rugby – 23 April 1915, Aegean Sea. The same paper has been chosen for the endpapers.

The paste-paper sides feature colours reminiscent of water or sky, along with those suggesting dirt and mud, in a repeating pattern by Victoria Hall. These are complemented with a goatskin leather quarter-binding in blue, blocked in gold with the poet’s name, and a coloured top-edge.

The poems have been typeset in Monotype Walbaum by Stan Lane at Gloucester Typesetting Services and printed hot-metal letterpress, along with six vignettes by Ed Kluz, at The Stonehouse Fine Press on Zerkall mould-made smooth paper. In addition to the vignettes, Ed Kluz has created nine four-colour illustrations to accompany the poems. These have been printed at Curwen Studios by autolithography – a process which produces an original artwork with every printing. The books have been bound by Legatoria Editoriale Giovanni Olivotto – L.E.G.O. – founded in 1900 by Pietro Olivotto and still run by the family today.