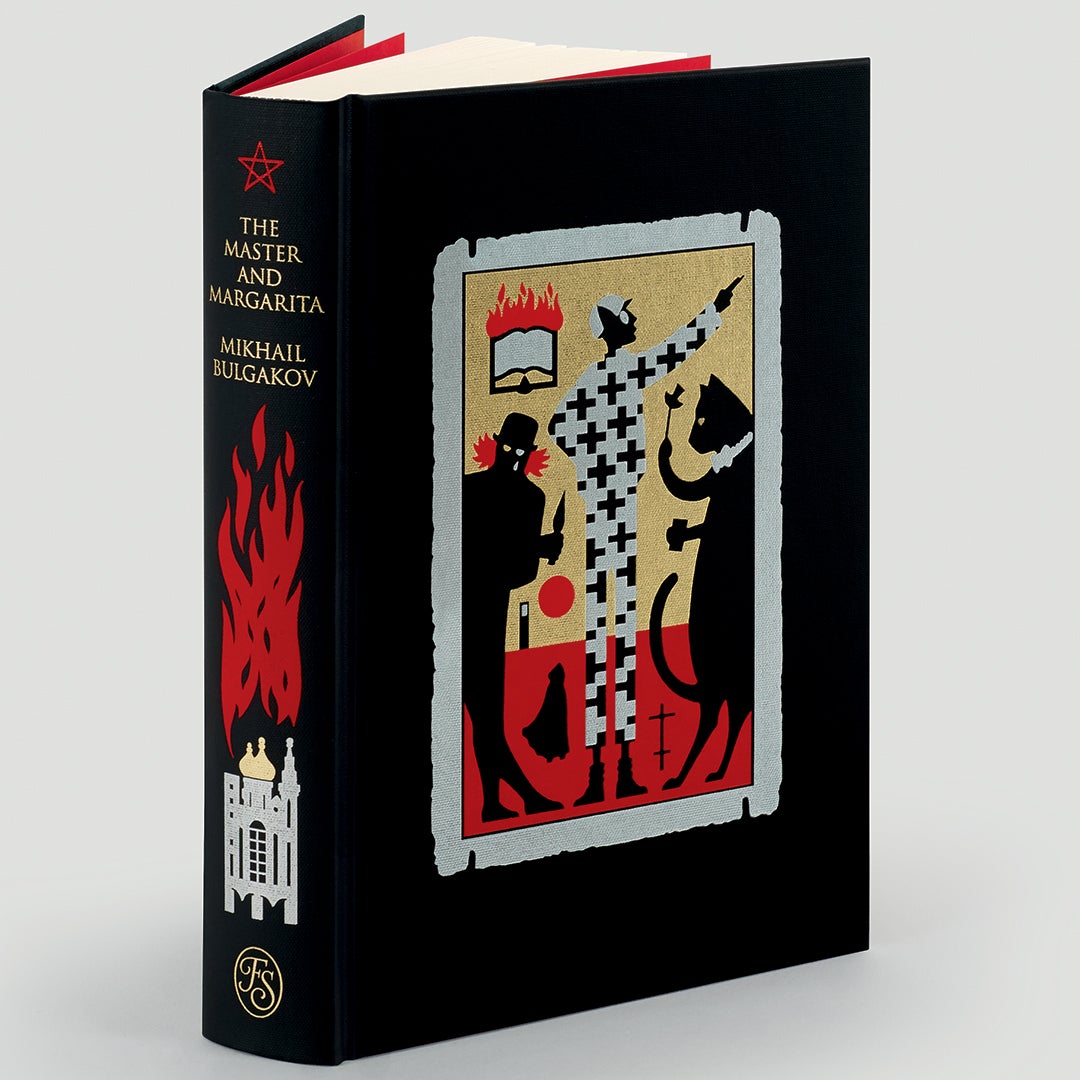

This Folio Life: To Serve Two Masters

Pictures in Books

A great part of the pleasure of illustrating novels is the reading of supporting material. Responding solely to the text is a choice; to read around the subject and draw on the lives and works of others, another. Charles Lamb in Last Essays of Elia: ‘I cannot sit and think. Books think for me.’ Books become pieces on a chequered board of thought and feeling about the work to be illuminated.

Mikhail Bulgakov (1891–1940)

To understand The Master and Margarita, read other works: A Dog’s Heart, A Country Doctor’s Notebook, The White Guard, The Fatal Eggs, A Dead Man’s Memoir; learn about Bulgakov’s life: the absurdity of the artist thwarted by the artless in power, the burning of the manuscript in 1930 and the subsequent recall and rewriting, Bulgakov’s work at the Moscow Arts Theatre, the censor, the jockeying for flats, the excruciating loss of integrity in making art within a system of nonsense, the tortured route to publication of Margarita, first published in parts in Moscow magazine in 1966/67, a spooky echo of the Master’s travails in the novel.

Russia

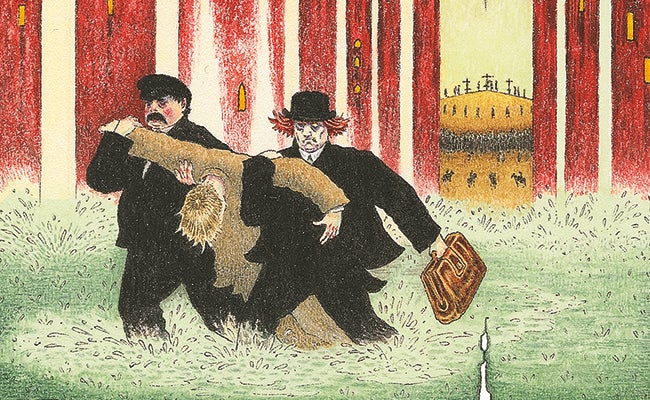

To understand Bulgakov, read about the Russian Revolution and the Soviet Union. During and after working on this book, a smattering of Russian literature: We, Envy, Eugene Onegin, Dead Souls, Nikolai Gogol (Nabokov’s poised English prose), A Hero of Our Time, Faust, Yakov Pasynkov, Fathers and Sons, The Slynx, Soul. Harry Lime’s speech on Switzerland, peace and the cuckoo clock, written (or passed on) by Welles, not Greene: Russia’s terrible suffering part of its wondrous art—Bulgakov, Stravinsky, Tarkovsky, Andrei Rublev. Russian Orthodox icons: rich in colour and texture and pattern, on weathered wooden boards. One trick adopted: the flat chequerboard of black-and-white crosses heedless of folds in the garments it adorns. (Flatness in pictures: the interplay of flat piece of paper and every mark’s inescapable suggestion of space; Jasper Johns’ flags and targets; Tom Wolfe’s The Painted Word.) Orthodox Christianity: old, deep, and grave.

The Master’s Novel

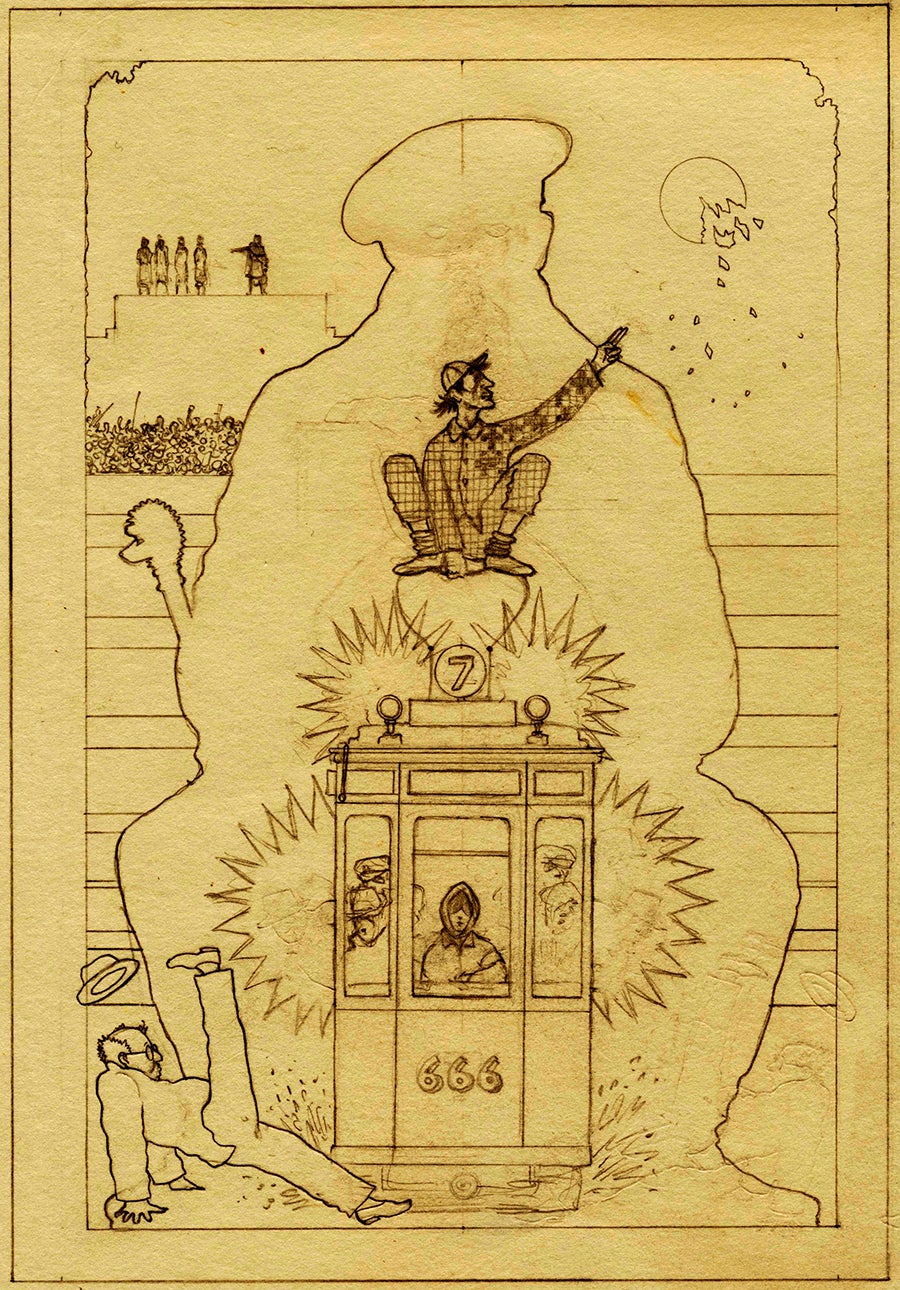

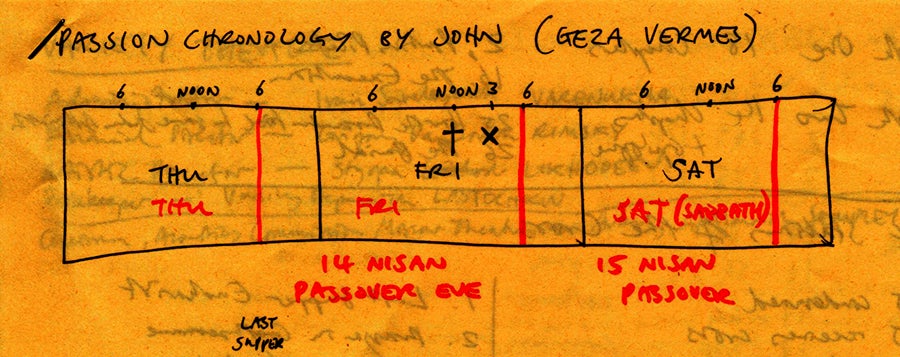

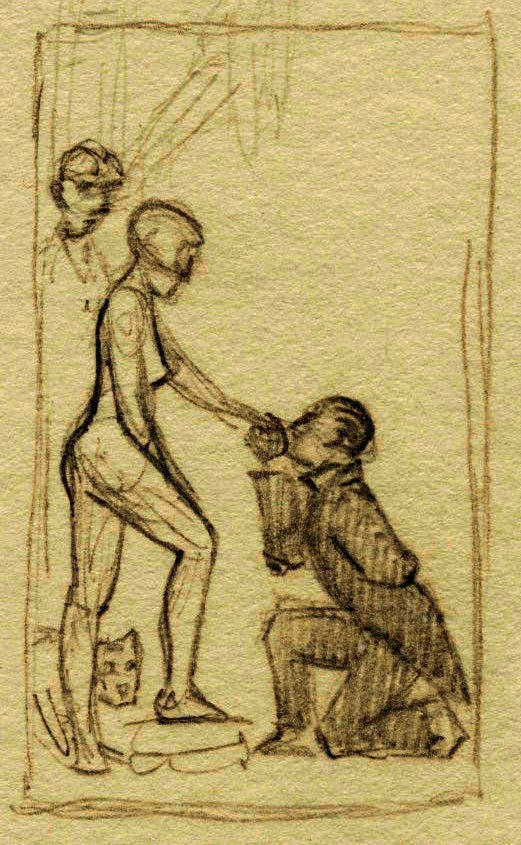

The fourteenth day of Nisan, cited in the Master’s book: what is it? Consult Geza Vermes’ The Nativity, The Passion, The Resurrection; Josephus’ The Jewish War; and the Four Gospels. 14 Nisan: the spring day before Passover, day-change being 6 pm, not midnight. A chronology constructed of the trial and murder of Jesus of Nazareth. The Master’s book on the death of Yeshua Ha-Nozri one of the great missing novels; just four tantalising chapters. Pilate’s headaches and loathing of rose oil; the command ‘To me!’; cowardice the most terrible vice; Yeshua ‘burnt on a post’. If only we could have it complete. (Do not, anyone, achieve that; a book as bootless as Titus Awakes.) Adjunctive to the main subject of the illustrations: the Master’s tale in the Stations of the Cross.

Faust

To understand one of the themes of Margarita, read Goethe and Marlowe. Goethe’s Part One more pleasurable than Part Two, just as the Inferno against the Paradiso. Heaven is unentertaining; what we want is the Devil, sorrow and destruction. Bulgakov’s masterful characterisation of Woland: urbane, elliptical, always looking side-stage; not from fear, but from lack of interest in whatever is before him. Watch Sokurov’s beautiful Faust (2011) and the way the tubby Devil glides his hat onto his head. In conversation with a football team-mate become doctor of German literature: if there is no God and no soul and no Devil, there is no trade, no salvation, no damnation. Science and knowledge are ours by striving. We have pulled ourselves up by our bootstraps.

Not in a Book

In addition to research, the memory of a train ride from Hong Kong to London in 1986. (An unsubstantiated report: Hong Kong used to be on the destination board at Victoria.) The cheapest ticket on the three-day train to Beijing meant sleeping sitting, until a fellow passenger pointed to a sheet of newspaper on the filthy floor beneath our seats: my turn to get two hours’ horizontal sleep. Beijing: breakfast at the Friendship Hotel, a picnic on a tower in the Wall, a punk at the British consulate, a wishing well in the Forbidden City. On an excursion to Inner Mongolia, under a vast sky blazing with stars, we saw gamblers intent on their cards through a smoky yellow window and borrowed their bike to explore. On the platform for the Russian Trans-Mongolian and Siberian to Moscow via Ulaanbaatar, dreams of Anna Karenina as cabin-mate, but he was a Viennese jazz pianist who smoked roll-ups in the corridor for six days, pining for his bohemian milieu, leaving me alone in the little moving room to read Graham Swift’s Waterland as Lake Baikal slid by. The time zones changed as we travelled, and no matter what my calculations the buffet car was always closed when dinner was sought, though reports of its being open drifted down the train like smoke. There was boiling water in the corridor to pour into a Chinese enamelled cup with a stencilled red rose, for tea between sittings in the Fens.

The border was a windswept barrenness. The Red Army invaded to inspect passports. The viewless wastes of the steppes, and then the Middle Urals. At Yaroslavsky Station in Moscow, strangers on the platform waved and greeted and deserted one by one until my taxi driver turned up. Spotting a pigeon in the road as we swept into the city, he accelerated his funny-car and feathers fanned over the windscreen before his expressionless face, his Moriarty fists clenched about the wheel. Glasnost and perestroika were in train, but the city and its eateries made me Winston Smith. St Basil’s was a luminous numinous cave. Viewing the pretence of Lenin’s body, the Red Army felt a cylinder of cough mixture in my pocket; an adroit miming of a raging throat forestalled the gulag. A stroll round the walkways, bridges and galleries of the department store GUM, Piranesi’s carceri d'invenzione, and a ride all the way round the Koltsevaya line on the metro, to see the art of decoration. On a walk from the hotel in the grim south of the city, Nabokov’s ‘confused and enthusiastic hullabaloo of bathing young villagers’ (Speak, Memory, 8.5) in a bend of river; still, in all this, you are here. A squat, bushy-browed hotel official, suspicious of a solo traveller and clearly from the KGB, who at breakfast had thrice sat me alone, miles from the chatting groups of other guests, looked at me under said brows and asked, ‘You are enjoying trip?’ ‘Yes.’ Tatyana Larina escorted me to the hotel sauna in the basement, but locked me in and her, out. A sealed room of chipped tiles, deep pools, steel apparatus and the likelihood of murder never detected. Near the Kremlin, the sound of jazz drums spilling from an upstairs window. Drunk in the hotel room raging against Stalin in a notebook, subsequently burnt, page by page.

At last a train, through Warsaw to Heaven (beer and Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin, coffee and cigarettes at the Café Central in Vienna, wine and evening sunlight in Siena) and London. The dying days of the Soviet Union. Mr Bulgakov: your book has buried it.

The Master’s Novel

Read The Master and Margarita for profound pleasure, for laughs, and for the soaring, plummeting, sounding transport of the imagination, an unalloyed good that giggles at any world-striding ideology.

This blog is by artist Peter Suart

At the Siege Perilous, spring 2021