This Folio Life: Mystery Train, Greil Marcus and Dorothea Lange

Greil Marcus on one of his favourite images from the Folio edition of Mystery Train, and the family connection to its photographer, the great Dorothea Lange.

Mandy Kirby, Non-Fiction Editor

In 2017, I walked into the Oakland Museum of California to visit its exhibition of work by Dorothea Lange, The Politics of Seeing. She was the most celebrated of San Francisco photographers; I was from San Francisco; I thought I knew her work. But here, blown up as a photo mural, was the opening image of the show, her 1939 Country Store. I’d never seen it before, not on a wall, not in a book.

I kept coming back to it, examining every advertisement, every face, every posture. At first look, and maybe last, too, it was a shining portrait of ease and camaraderie between a white store owner and five young black men – he standing in the doorway, they seated on chairs on the store porch. The store owner looks down at the man seated second from the left, a metal Coca-Cola sign above his head, who has a bottle raised to his mouth, as if to see what the customer thinks of the new soft drink the establishment has just brought in – and everybody else might be asking the same question. You can easily decode the picture as an examination of the false consciousness the cultural superstructure imposes on the plain class-conflict inherent in any encounter between a petit-bourgeois capitalist and members of the agricultural proletariat – for all we know, that might have been part of what Dorothea Lange saw when she made the picture. What I saw, and what I took away, was a portrait of American democracy.

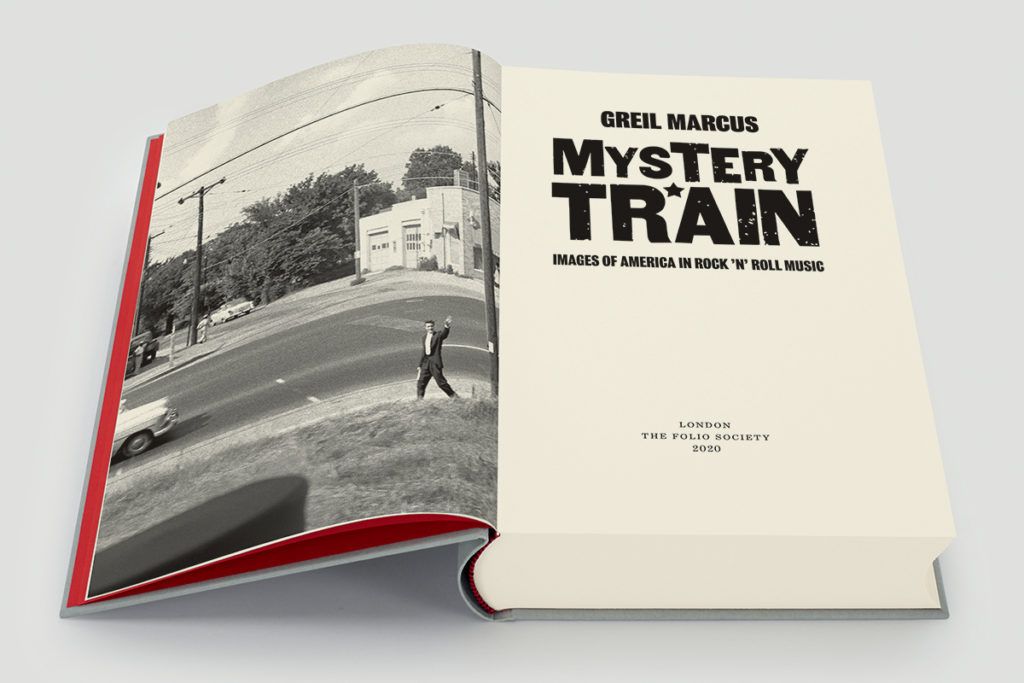

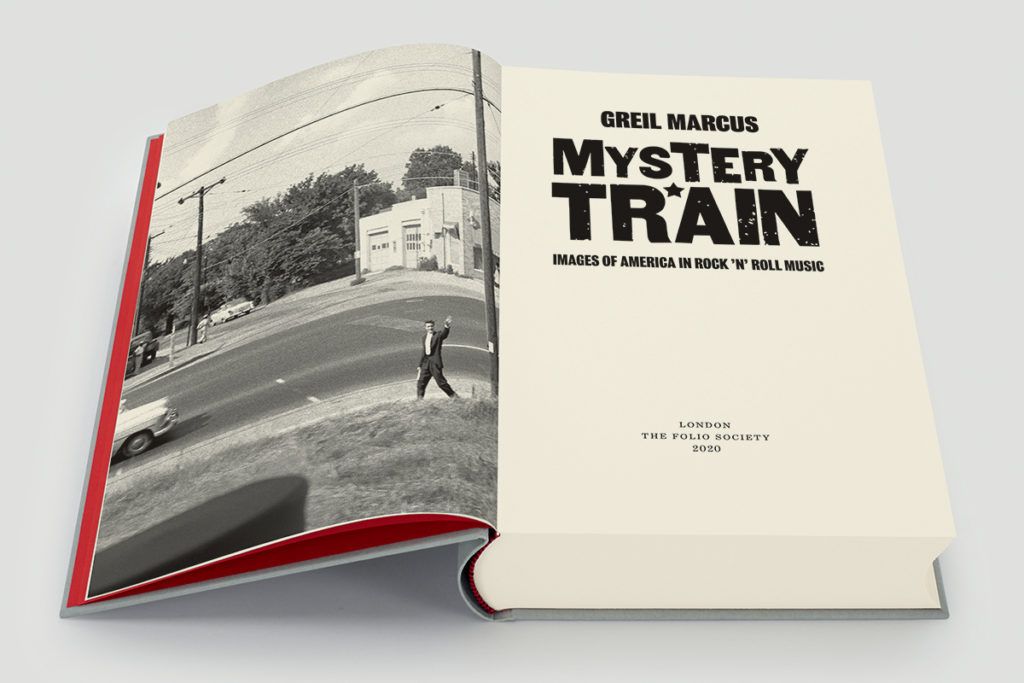

When I was approached by The Folio Society about an illustrated edition of my 1975 book Mystery Train, I asked them to take the idea and run with it: make it happen on their own terms, let the book, not me, tell them what illustrations to use.

As it happens, when I was working on the original edition of the book, someone asked me if there would be any pictures. I said no, but I immediately thought that if there ever were, they should just be public domain works from the Farm Security Administration photographers – Lange, Walker Evans, Ben Shahn, Gordon Parks, and others – dispatched by the U.S. government, mainly to the south, to document the daily life of Americans under the Great Depression. And beyond strictly narrative illustrations, that, by somehow intuiting not so much what I had wanted but what, on its own terms, the book still wanted, was what The Folio Society came up with. One image that was missing was Lange’s Country Store; I asked if it could be added to the portfolio they had already assembled. So here it is, after Elvis waving in Memphis twenty-seven years later, opening the book.

I kept coming back to it, examining every advertisement, every face, every posture. At first look, and maybe last, too, it was a shining portrait of ease and camaraderie between a white store owner and five young black men – he standing in the doorway, they seated on chairs on the store porch. The store owner looks down at the man seated second from the left, a metal Coca-Cola sign above his head, who has a bottle raised to his mouth, as if to see what the customer thinks of the new soft drink the establishment has just brought in – and everybody else might be asking the same question. You can easily decode the picture as an examination of the false consciousness the cultural superstructure imposes on the plain class-conflict inherent in any encounter between a petit-bourgeois capitalist and members of the agricultural proletariat – for all we know, that might have been part of what Dorothea Lange saw when she made the picture. What I saw, and what I took away, was a portrait of American democracy.

When I was approached by The Folio Society about an illustrated edition of my 1975 book Mystery Train, I asked them to take the idea and run with it: make it happen on their own terms, let the book, not me, tell them what illustrations to use.

As it happens, when I was working on the original edition of the book, someone asked me if there would be any pictures. I said no, but I immediately thought that if there ever were, they should just be public domain works from the Farm Security Administration photographers – Lange, Walker Evans, Ben Shahn, Gordon Parks, and others – dispatched by the U.S. government, mainly to the south, to document the daily life of Americans under the Great Depression. And beyond strictly narrative illustrations, that, by somehow intuiting not so much what I had wanted but what, on its own terms, the book still wanted, was what The Folio Society came up with. One image that was missing was Lange’s Country Store; I asked if it could be added to the portfolio they had already assembled. So here it is, after Elvis waving in Memphis twenty-seven years later, opening the book.

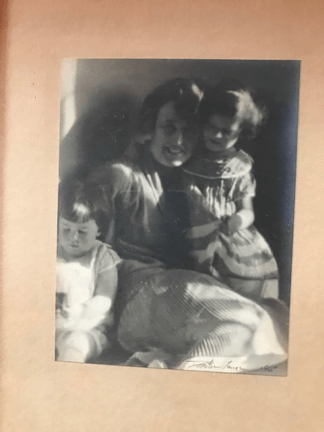

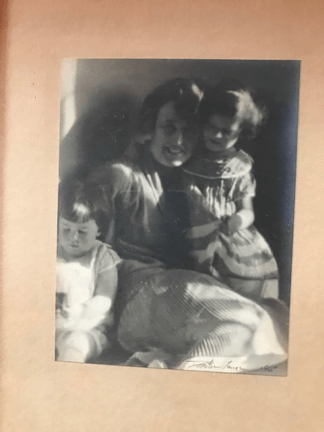

But there was something else I didn’t know about Dorothea Lange. Some years before the Oakland exhibition, I saw a family photograph that I’d never noticed before in my parents’ house in Menlo Park, just down the Peninsula from San Francisco. I was struck by the balance of the composition – the way there was an undeniable center to the picture, yet with an element that pulled away. It was familiar – the center was my grandmother, Helen Hyman, born in Portland in 1892, then her early thirties, and her oldest daughter, Elizabeth, my aunt, born in San Francisco in 1920, then about five; the part of the picture that was pulling away was my mother, Eleanore, born in San Francisco in 1923, then about two. My mother was no longer talking when I found the picture, but I took it to her and asked her if she knew when it was made and if she knew who took it. She smiled and pointed to a light pencil signature in the bottom right corner: Dorothea Lange, 1925.

But there was something else I didn’t know about Dorothea Lange. Some years before the Oakland exhibition, I saw a family photograph that I’d never noticed before in my parents’ house in Menlo Park, just down the Peninsula from San Francisco. I was struck by the balance of the composition – the way there was an undeniable center to the picture, yet with an element that pulled away. It was familiar – the center was my grandmother, Helen Hyman, born in Portland in 1892, then her early thirties, and her oldest daughter, Elizabeth, my aunt, born in San Francisco in 1920, then about five; the part of the picture that was pulling away was my mother, Eleanore, born in San Francisco in 1923, then about two. My mother was no longer talking when I found the picture, but I took it to her and asked her if she knew when it was made and if she knew who took it. She smiled and pointed to a light pencil signature in the bottom right corner: Dorothea Lange, 1925.

As a young photographer in San Francisco, Lange made her living taking photos like these – except that they weren’t the usual family pictures you paid a photographer catering to professional families in a sophisticated city to take. You expect the smiling mother and her daughter perched comfortably on her mother’s lap, her arm on her shoulder; you don’t expect a second, younger daughter, turned away, looking at a toy in her hands, in her own world, or in any case not in the world of the family the picture is supposed to represent, but didn’t.

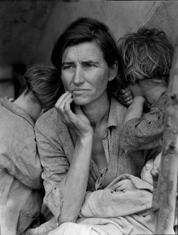

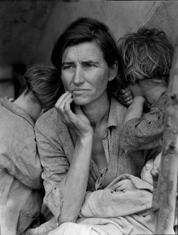

As with the picture of the men at the country store, a lot is going on here. The shock of recognition I had when I first saw the picture was two-fold. First, I saw my mother, as barely a child, as the person she would become: “fragile,” as she was described when she was twenty and first married, pursued by her own depression through the next decades, finally suicidal. Growing up, I assumed all kids got home from school to find their mothers lying in bed in a darkened room. All of that was present, like a flashbulb going off eighty years after the fact, in Lange’s picture – but also present was Lange’s most famous photograph, Migrant Mother, taken in 1936, at a migrant worker’s camp in San Luis Obispo County. It would become the most famous photograph of the Depression: a mother at the center, two children burying their faces behind either of her shoulders, and a baby in her lap – sleeping, but, with the dirt on its face and the loll of the head, your first impression can be that the baby is dead. Gone. She is already somewhere else.

As a young photographer in San Francisco, Lange made her living taking photos like these – except that they weren’t the usual family pictures you paid a photographer catering to professional families in a sophisticated city to take. You expect the smiling mother and her daughter perched comfortably on her mother’s lap, her arm on her shoulder; you don’t expect a second, younger daughter, turned away, looking at a toy in her hands, in her own world, or in any case not in the world of the family the picture is supposed to represent, but didn’t.

As with the picture of the men at the country store, a lot is going on here. The shock of recognition I had when I first saw the picture was two-fold. First, I saw my mother, as barely a child, as the person she would become: “fragile,” as she was described when she was twenty and first married, pursued by her own depression through the next decades, finally suicidal. Growing up, I assumed all kids got home from school to find their mothers lying in bed in a darkened room. All of that was present, like a flashbulb going off eighty years after the fact, in Lange’s picture – but also present was Lange’s most famous photograph, Migrant Mother, taken in 1936, at a migrant worker’s camp in San Luis Obispo County. It would become the most famous photograph of the Depression: a mother at the center, two children burying their faces behind either of her shoulders, and a baby in her lap – sleeping, but, with the dirt on its face and the loll of the head, your first impression can be that the baby is dead. Gone. She is already somewhere else.

What was at work in both photographs – Lange took at least six pictures of Florence Thompson and her children in the camp at Nipomo that day, and printed at least three more from her visit to my grandmother’s Jackson Street house in San Francisco – was Lange’s eye. Her first eye – what in blues music would be called her first mind – looked for and constructed a center of gravity. But her second eye – her second mind – looked for discontinuity, displacement, a gravitational pull away from ordinary symmetry, which pulls the picture itself away from what would appear to be its subject.

The first subject in Migrant Mother is Florence Thompson’s handsome, worried face, her eyes gazing into a near-future that refuses to come into focus. The first subject in the picture of my grandmother’s family is the proud mother and her safe, protected daughter. The second subject, in both pictures, is that of the youngest child, who seems part of another story altogether – a child who cannot be protected, or who doesn’t want to be.

Plainly, my grandmother did not look over the photographs and say, “Miss Lange, this is not the sort of picture I was hoping to receive; we are a happy family.” My grandmother was a grandiose and spectacular woman, but she flinched from very little. She must have known that in whatever way, for whatever reason, Lange had seen and told the truth, even if, as has been said of another parent, she “wasn’t so sure the truth would set anybody free.”

This blog was written by author Greil Marcus.

What was at work in both photographs – Lange took at least six pictures of Florence Thompson and her children in the camp at Nipomo that day, and printed at least three more from her visit to my grandmother’s Jackson Street house in San Francisco – was Lange’s eye. Her first eye – what in blues music would be called her first mind – looked for and constructed a center of gravity. But her second eye – her second mind – looked for discontinuity, displacement, a gravitational pull away from ordinary symmetry, which pulls the picture itself away from what would appear to be its subject.

The first subject in Migrant Mother is Florence Thompson’s handsome, worried face, her eyes gazing into a near-future that refuses to come into focus. The first subject in the picture of my grandmother’s family is the proud mother and her safe, protected daughter. The second subject, in both pictures, is that of the youngest child, who seems part of another story altogether – a child who cannot be protected, or who doesn’t want to be.

Plainly, my grandmother did not look over the photographs and say, “Miss Lange, this is not the sort of picture I was hoping to receive; we are a happy family.” My grandmother was a grandiose and spectacular woman, but she flinched from very little. She must have known that in whatever way, for whatever reason, Lange had seen and told the truth, even if, as has been said of another parent, she “wasn’t so sure the truth would set anybody free.”

This blog was written by author Greil Marcus.

Find out more and order Mystery Train

Find out more and order Mystery Train

I kept coming back to it, examining every advertisement, every face, every posture. At first look, and maybe last, too, it was a shining portrait of ease and camaraderie between a white store owner and five young black men – he standing in the doorway, they seated on chairs on the store porch. The store owner looks down at the man seated second from the left, a metal Coca-Cola sign above his head, who has a bottle raised to his mouth, as if to see what the customer thinks of the new soft drink the establishment has just brought in – and everybody else might be asking the same question. You can easily decode the picture as an examination of the false consciousness the cultural superstructure imposes on the plain class-conflict inherent in any encounter between a petit-bourgeois capitalist and members of the agricultural proletariat – for all we know, that might have been part of what Dorothea Lange saw when she made the picture. What I saw, and what I took away, was a portrait of American democracy.

When I was approached by The Folio Society about an illustrated edition of my 1975 book Mystery Train, I asked them to take the idea and run with it: make it happen on their own terms, let the book, not me, tell them what illustrations to use.

As it happens, when I was working on the original edition of the book, someone asked me if there would be any pictures. I said no, but I immediately thought that if there ever were, they should just be public domain works from the Farm Security Administration photographers – Lange, Walker Evans, Ben Shahn, Gordon Parks, and others – dispatched by the U.S. government, mainly to the south, to document the daily life of Americans under the Great Depression. And beyond strictly narrative illustrations, that, by somehow intuiting not so much what I had wanted but what, on its own terms, the book still wanted, was what The Folio Society came up with. One image that was missing was Lange’s Country Store; I asked if it could be added to the portfolio they had already assembled. So here it is, after Elvis waving in Memphis twenty-seven years later, opening the book.

I kept coming back to it, examining every advertisement, every face, every posture. At first look, and maybe last, too, it was a shining portrait of ease and camaraderie between a white store owner and five young black men – he standing in the doorway, they seated on chairs on the store porch. The store owner looks down at the man seated second from the left, a metal Coca-Cola sign above his head, who has a bottle raised to his mouth, as if to see what the customer thinks of the new soft drink the establishment has just brought in – and everybody else might be asking the same question. You can easily decode the picture as an examination of the false consciousness the cultural superstructure imposes on the plain class-conflict inherent in any encounter between a petit-bourgeois capitalist and members of the agricultural proletariat – for all we know, that might have been part of what Dorothea Lange saw when she made the picture. What I saw, and what I took away, was a portrait of American democracy.

When I was approached by The Folio Society about an illustrated edition of my 1975 book Mystery Train, I asked them to take the idea and run with it: make it happen on their own terms, let the book, not me, tell them what illustrations to use.

As it happens, when I was working on the original edition of the book, someone asked me if there would be any pictures. I said no, but I immediately thought that if there ever were, they should just be public domain works from the Farm Security Administration photographers – Lange, Walker Evans, Ben Shahn, Gordon Parks, and others – dispatched by the U.S. government, mainly to the south, to document the daily life of Americans under the Great Depression. And beyond strictly narrative illustrations, that, by somehow intuiting not so much what I had wanted but what, on its own terms, the book still wanted, was what The Folio Society came up with. One image that was missing was Lange’s Country Store; I asked if it could be added to the portfolio they had already assembled. So here it is, after Elvis waving in Memphis twenty-seven years later, opening the book.

But there was something else I didn’t know about Dorothea Lange. Some years before the Oakland exhibition, I saw a family photograph that I’d never noticed before in my parents’ house in Menlo Park, just down the Peninsula from San Francisco. I was struck by the balance of the composition – the way there was an undeniable center to the picture, yet with an element that pulled away. It was familiar – the center was my grandmother, Helen Hyman, born in Portland in 1892, then her early thirties, and her oldest daughter, Elizabeth, my aunt, born in San Francisco in 1920, then about five; the part of the picture that was pulling away was my mother, Eleanore, born in San Francisco in 1923, then about two. My mother was no longer talking when I found the picture, but I took it to her and asked her if she knew when it was made and if she knew who took it. She smiled and pointed to a light pencil signature in the bottom right corner: Dorothea Lange, 1925.

But there was something else I didn’t know about Dorothea Lange. Some years before the Oakland exhibition, I saw a family photograph that I’d never noticed before in my parents’ house in Menlo Park, just down the Peninsula from San Francisco. I was struck by the balance of the composition – the way there was an undeniable center to the picture, yet with an element that pulled away. It was familiar – the center was my grandmother, Helen Hyman, born in Portland in 1892, then her early thirties, and her oldest daughter, Elizabeth, my aunt, born in San Francisco in 1920, then about five; the part of the picture that was pulling away was my mother, Eleanore, born in San Francisco in 1923, then about two. My mother was no longer talking when I found the picture, but I took it to her and asked her if she knew when it was made and if she knew who took it. She smiled and pointed to a light pencil signature in the bottom right corner: Dorothea Lange, 1925.

As a young photographer in San Francisco, Lange made her living taking photos like these – except that they weren’t the usual family pictures you paid a photographer catering to professional families in a sophisticated city to take. You expect the smiling mother and her daughter perched comfortably on her mother’s lap, her arm on her shoulder; you don’t expect a second, younger daughter, turned away, looking at a toy in her hands, in her own world, or in any case not in the world of the family the picture is supposed to represent, but didn’t.

As with the picture of the men at the country store, a lot is going on here. The shock of recognition I had when I first saw the picture was two-fold. First, I saw my mother, as barely a child, as the person she would become: “fragile,” as she was described when she was twenty and first married, pursued by her own depression through the next decades, finally suicidal. Growing up, I assumed all kids got home from school to find their mothers lying in bed in a darkened room. All of that was present, like a flashbulb going off eighty years after the fact, in Lange’s picture – but also present was Lange’s most famous photograph, Migrant Mother, taken in 1936, at a migrant worker’s camp in San Luis Obispo County. It would become the most famous photograph of the Depression: a mother at the center, two children burying their faces behind either of her shoulders, and a baby in her lap – sleeping, but, with the dirt on its face and the loll of the head, your first impression can be that the baby is dead. Gone. She is already somewhere else.

As a young photographer in San Francisco, Lange made her living taking photos like these – except that they weren’t the usual family pictures you paid a photographer catering to professional families in a sophisticated city to take. You expect the smiling mother and her daughter perched comfortably on her mother’s lap, her arm on her shoulder; you don’t expect a second, younger daughter, turned away, looking at a toy in her hands, in her own world, or in any case not in the world of the family the picture is supposed to represent, but didn’t.

As with the picture of the men at the country store, a lot is going on here. The shock of recognition I had when I first saw the picture was two-fold. First, I saw my mother, as barely a child, as the person she would become: “fragile,” as she was described when she was twenty and first married, pursued by her own depression through the next decades, finally suicidal. Growing up, I assumed all kids got home from school to find their mothers lying in bed in a darkened room. All of that was present, like a flashbulb going off eighty years after the fact, in Lange’s picture – but also present was Lange’s most famous photograph, Migrant Mother, taken in 1936, at a migrant worker’s camp in San Luis Obispo County. It would become the most famous photograph of the Depression: a mother at the center, two children burying their faces behind either of her shoulders, and a baby in her lap – sleeping, but, with the dirt on its face and the loll of the head, your first impression can be that the baby is dead. Gone. She is already somewhere else.

What was at work in both photographs – Lange took at least six pictures of Florence Thompson and her children in the camp at Nipomo that day, and printed at least three more from her visit to my grandmother’s Jackson Street house in San Francisco – was Lange’s eye. Her first eye – what in blues music would be called her first mind – looked for and constructed a center of gravity. But her second eye – her second mind – looked for discontinuity, displacement, a gravitational pull away from ordinary symmetry, which pulls the picture itself away from what would appear to be its subject.

The first subject in Migrant Mother is Florence Thompson’s handsome, worried face, her eyes gazing into a near-future that refuses to come into focus. The first subject in the picture of my grandmother’s family is the proud mother and her safe, protected daughter. The second subject, in both pictures, is that of the youngest child, who seems part of another story altogether – a child who cannot be protected, or who doesn’t want to be.

Plainly, my grandmother did not look over the photographs and say, “Miss Lange, this is not the sort of picture I was hoping to receive; we are a happy family.” My grandmother was a grandiose and spectacular woman, but she flinched from very little. She must have known that in whatever way, for whatever reason, Lange had seen and told the truth, even if, as has been said of another parent, she “wasn’t so sure the truth would set anybody free.”

This blog was written by author Greil Marcus.

What was at work in both photographs – Lange took at least six pictures of Florence Thompson and her children in the camp at Nipomo that day, and printed at least three more from her visit to my grandmother’s Jackson Street house in San Francisco – was Lange’s eye. Her first eye – what in blues music would be called her first mind – looked for and constructed a center of gravity. But her second eye – her second mind – looked for discontinuity, displacement, a gravitational pull away from ordinary symmetry, which pulls the picture itself away from what would appear to be its subject.

The first subject in Migrant Mother is Florence Thompson’s handsome, worried face, her eyes gazing into a near-future that refuses to come into focus. The first subject in the picture of my grandmother’s family is the proud mother and her safe, protected daughter. The second subject, in both pictures, is that of the youngest child, who seems part of another story altogether – a child who cannot be protected, or who doesn’t want to be.

Plainly, my grandmother did not look over the photographs and say, “Miss Lange, this is not the sort of picture I was hoping to receive; we are a happy family.” My grandmother was a grandiose and spectacular woman, but she flinched from very little. She must have known that in whatever way, for whatever reason, Lange had seen and told the truth, even if, as has been said of another parent, she “wasn’t so sure the truth would set anybody free.”

This blog was written by author Greil Marcus.

Find out more and order Mystery Train

Find out more and order Mystery Train