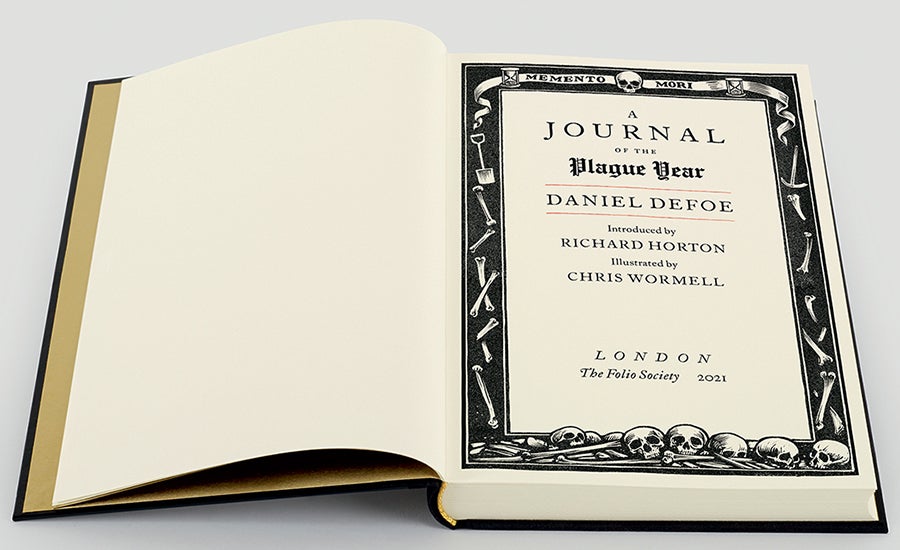

This Folio Life: A Journal of the Plague Year revisited

By Mandy Kirkby, Non-Fiction Publisher

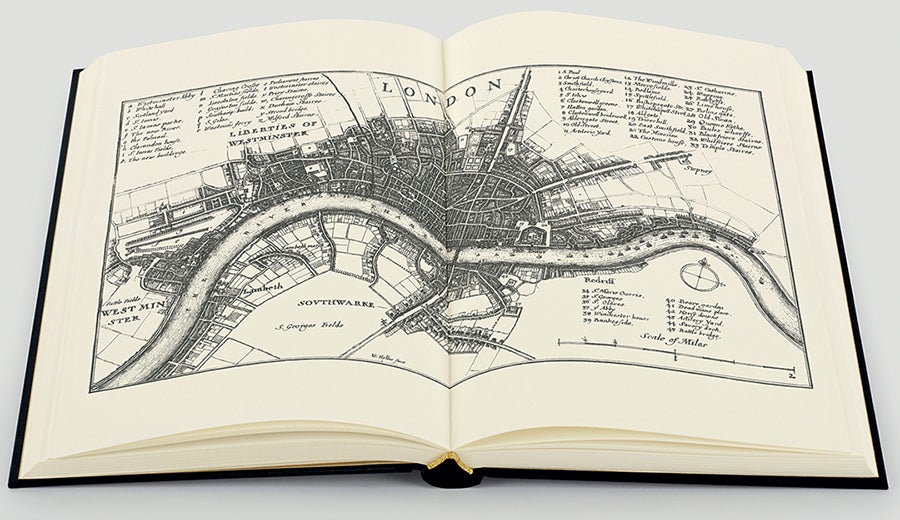

I first read Daniel Defoe's A Journal of the Plague Year back in the 1990s when I worked at the north end of Covent Garden, close to Drury Lane, which was where the first cases of the 1665 plague were recorded. I still have my old copy, in the small-format Penguin Classics livery, with the cover image detail of a George Cruikshank drawing of a 'A Great Plague dead cart' wending its way through the streets. Halfway down the first page: '...two men, said to be Frenchmen, died of the plague in Long Acre, or rather at the upper end of Drury Lane'. These were the first cases, and the infections increased considerably, quickly spreading from this parish (St Giles-in-the-Fields) to the neighbouring parish of St Andrew's in Holborn, and onwards across London with lightning speed.

Many a lunch hour would see me wandering around the area with Defoe's book and a map, trying to match the streets and buildings in his account with the modern layout and reconfigured placenames. To think that the first victims of the plague were buried in the churchyard of St Giles where I would eat my lunchtime sandwich, and hundreds more were buried there before the epidemic finally petered out.

Last year, the urge to revisit the book in the light of the current epidemic was impossible to resist. How would Defoe's account appear to us now? Still far, far away in the mists of time, like a dark and tragic period drama, a historical curiosity?

Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet medical journal had been writing regularly about Covid-19 throughout 2020, and he seemed the perfect person to introduce the new Folio edition. Here's an extract from his introduction, where he compares the old and modern plagues:

‘Coronavirus has introduced us to the idea of lockdowns – the complete closure of public life – as a means to sever lines of infectious transmission when an epidemic runs exponentially out of control. Lockdowns were deployed extensively during the Great Plague. Theatres, dancing rooms and music houses were shuttered. Beyond this, and reminiscent of modern-day measures, there was improved surveillance to discover sites of infection, the gathering of more reliable data, reduction of opportunities for contact with objects that might be harbouring the infection (such as money), the wearing of masks, enforcement with fines, and physical distancing ("the best physic against the plague is to run away from it"). London became desolate, a phantom of its former self. The same phenomenon struck the capital in 2020. Buses and trains were empty. The streets silent. Office buildings uninhabited. For several months, the city became a sterile mass of concrete, glass and steel. Barren, bleak and bare.’

The similarities on the ground are startling, as is the familiarity of Defoe's summing up of the whole tragedy. Here's Richard Horton again:

'Defoe offered his country a brief moment of clarity. He conveyed the true and unequal nature of his society. People were "in a condition so perfectly unprepared for such a dreadful visitation, whether I am to speak of the civil preparations, or religious." His profoundly human story revealed how the plague targeted and punished the vulnerable and poor. Defoe drew those who were usually unheard and unseen into the centre of political and public discussion. His Journal was an explicit call for solidarity in the face of a catastrophic threat. Defoe’s message is undoubtedly for today.’

Defoe's 'melancholy year' was also our melancholy year...

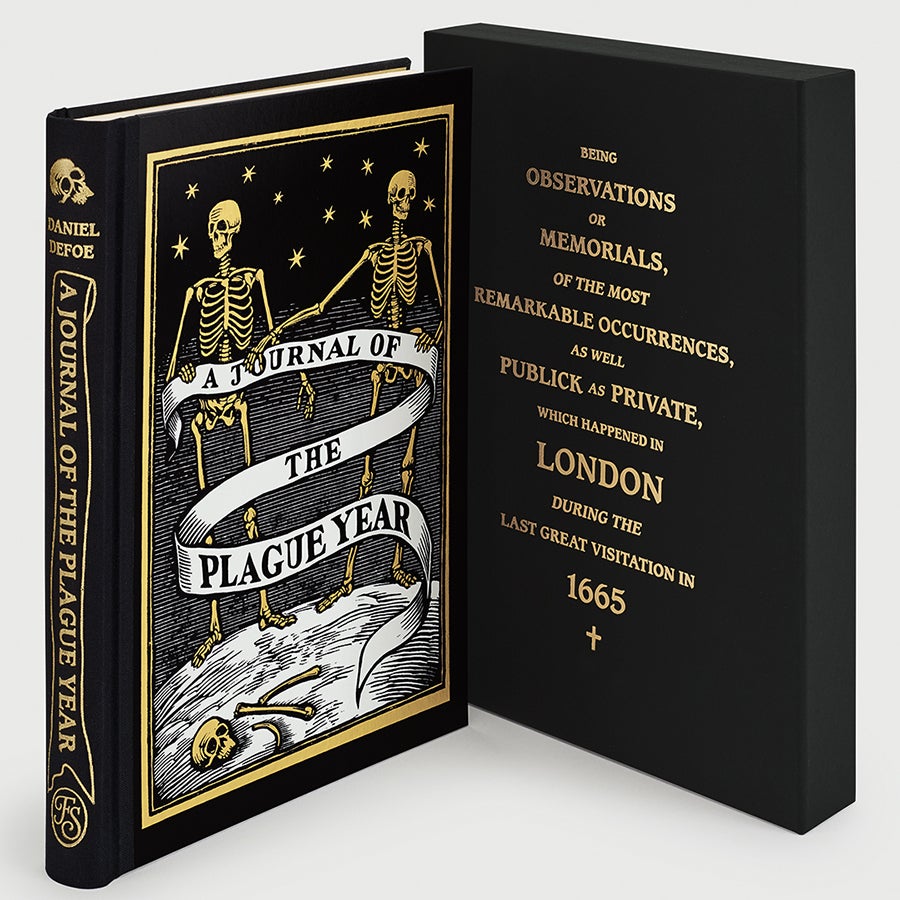

Find out more and order A Journal of the Plague Year