The Folio Life: Peter Forster (1934–2021)

Peter Forster, who died in January, was one of the outstanding wood engravers of the late 20th century. Much of his best work was produced for the Folio Society: between 1986 and 2003 he illustrated seven complete Folio volumes and contributed to three multi-artist publications.

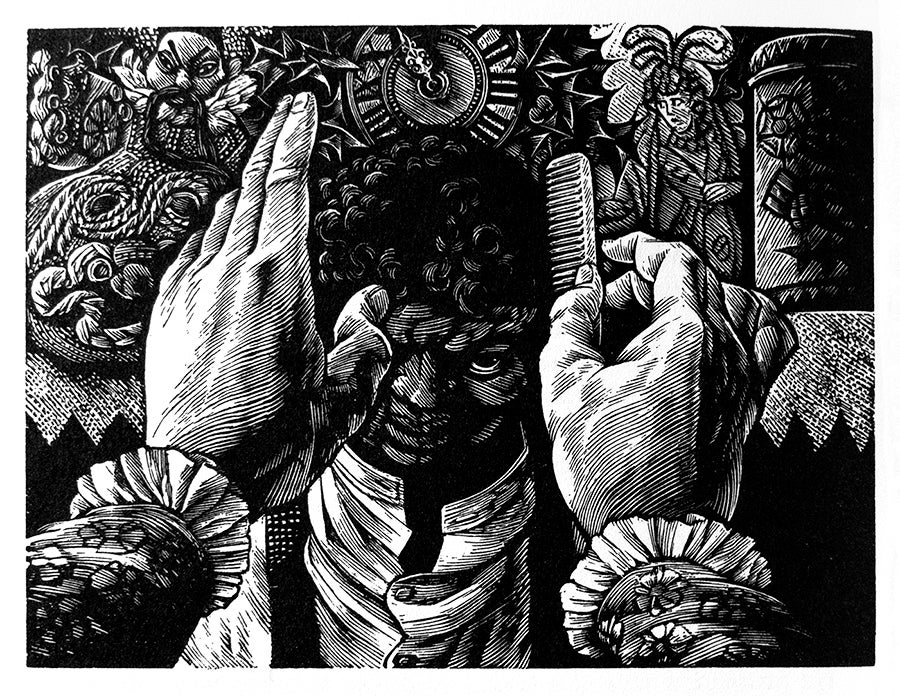

The first of these was Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, for which Peter cut three engravings. Here is the one from the Oxford Scholar's Tale (otherwise known as the Clerk's Tale), the story of patient Griselda, a young woman whose husband tests her loyalty in a series of cruel torments. In this engraving we see at once that Peter shuns a conventional illustrative approach; he depicts the faithful wife's subjugation through a powerful and complex image, unconstrained by such surface details as the time, place or plot of the story:

The chain attaching Griselda to her kennel forms the letter W – for Wedlock, presumably, whose chains are proverbial.

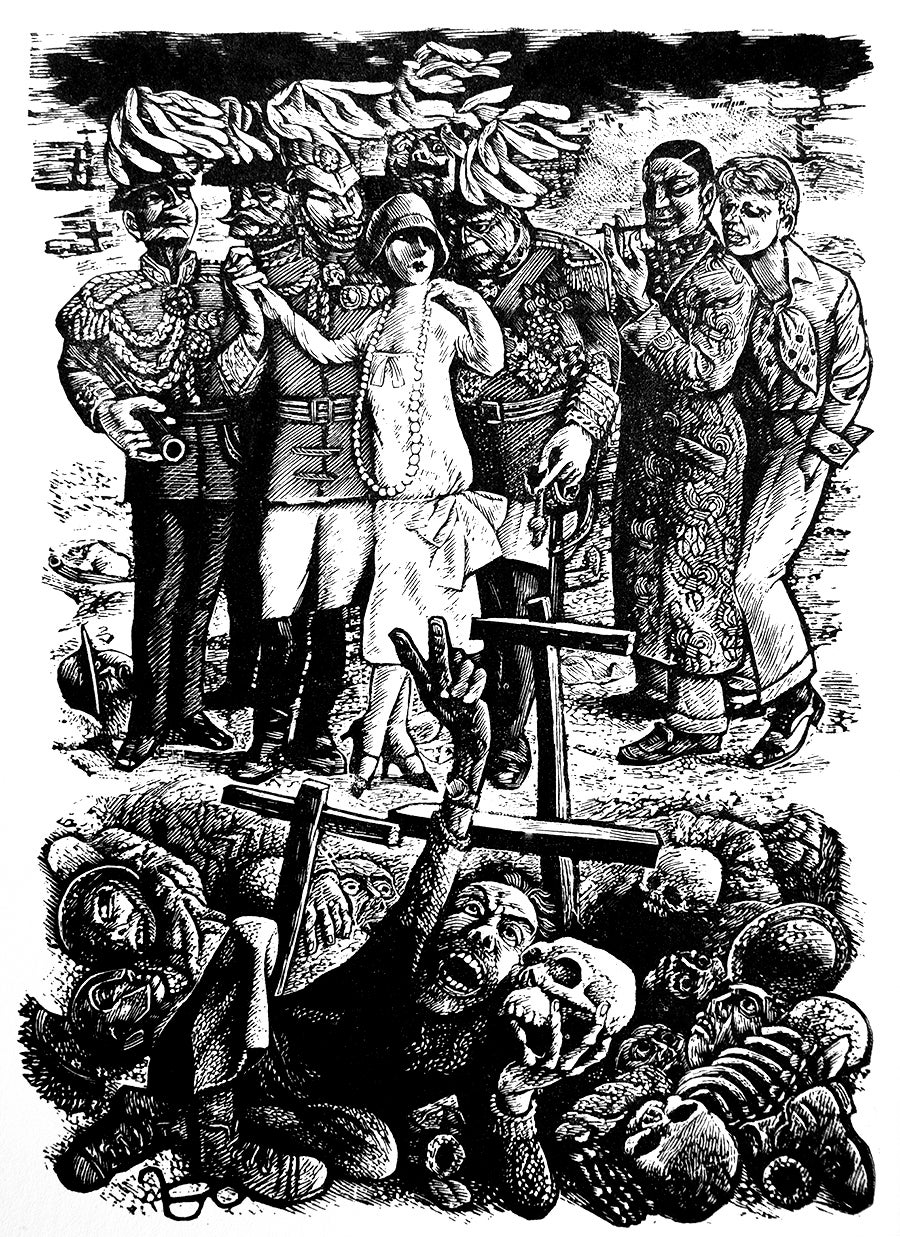

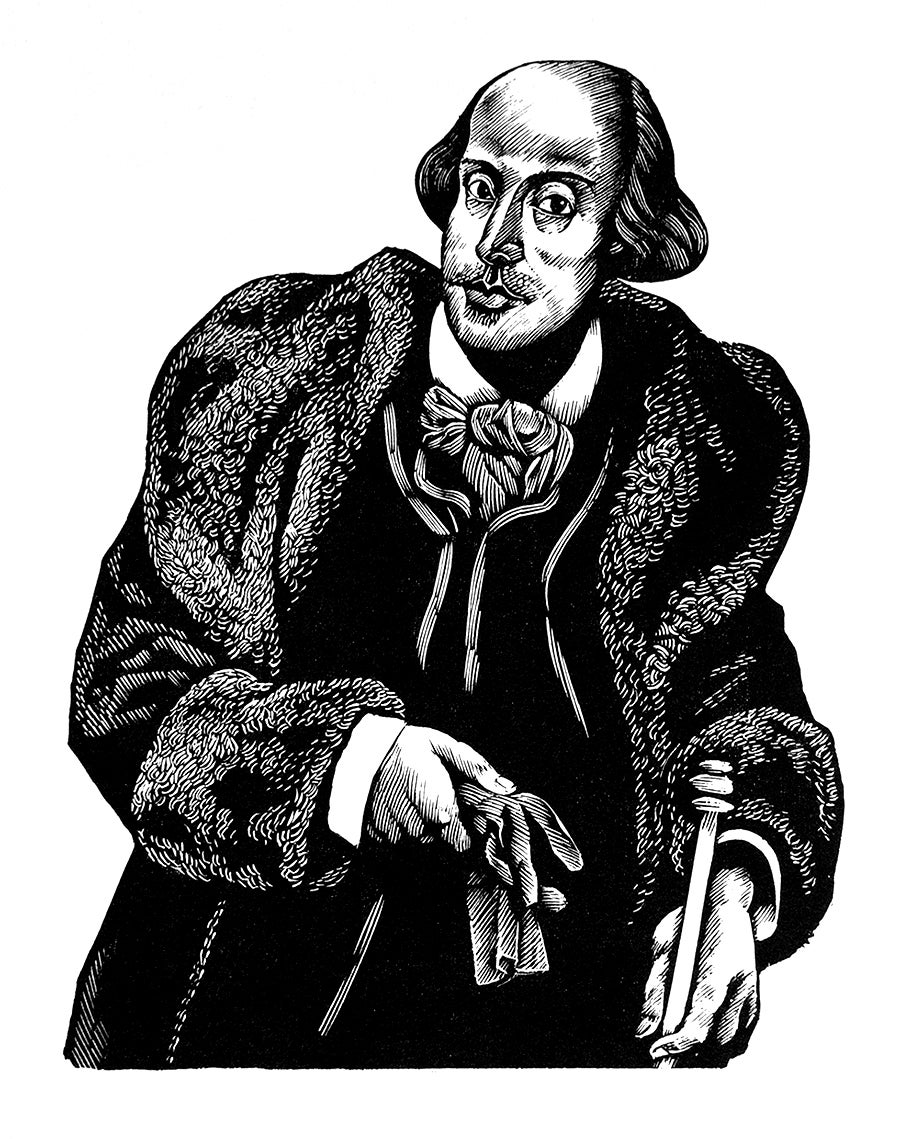

The Folio Shakespeare, published in 1988, featured the work of no fewer than 19 engravers, each of whom provided a frontispiece to two (or sometimes three) plays. Troilus and Cressida was one of Peter's:

In a letter to one of his collectors, Peter wrote: 'The only portrait in it is the Thersites, who is me.' This is surprising, since the general on the left bears a strong resemblance to Sir John Gielgud, and the gentleman in the dressing-gown is surely Noel Coward (though the identity of his partner is a mystery – I'd be grateful for any enlightenment on this). The four generals clustered around Cressida may be the four emperors, three of whom were first cousins, who ruled most of Europe at the outbreak of World War One; certainly the one peering over Cressida's head looks suspiciously like Kaiser Wilhelm.

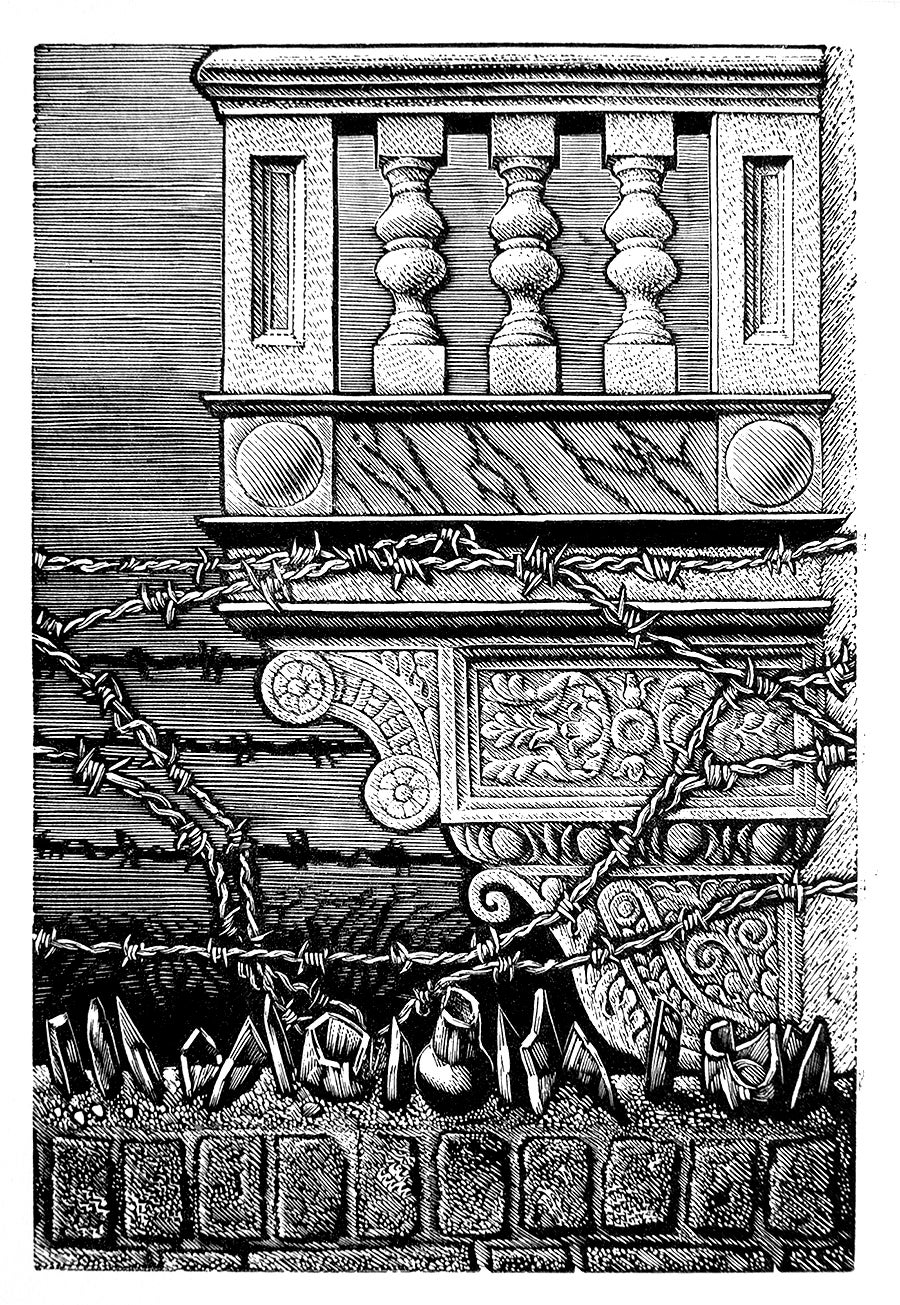

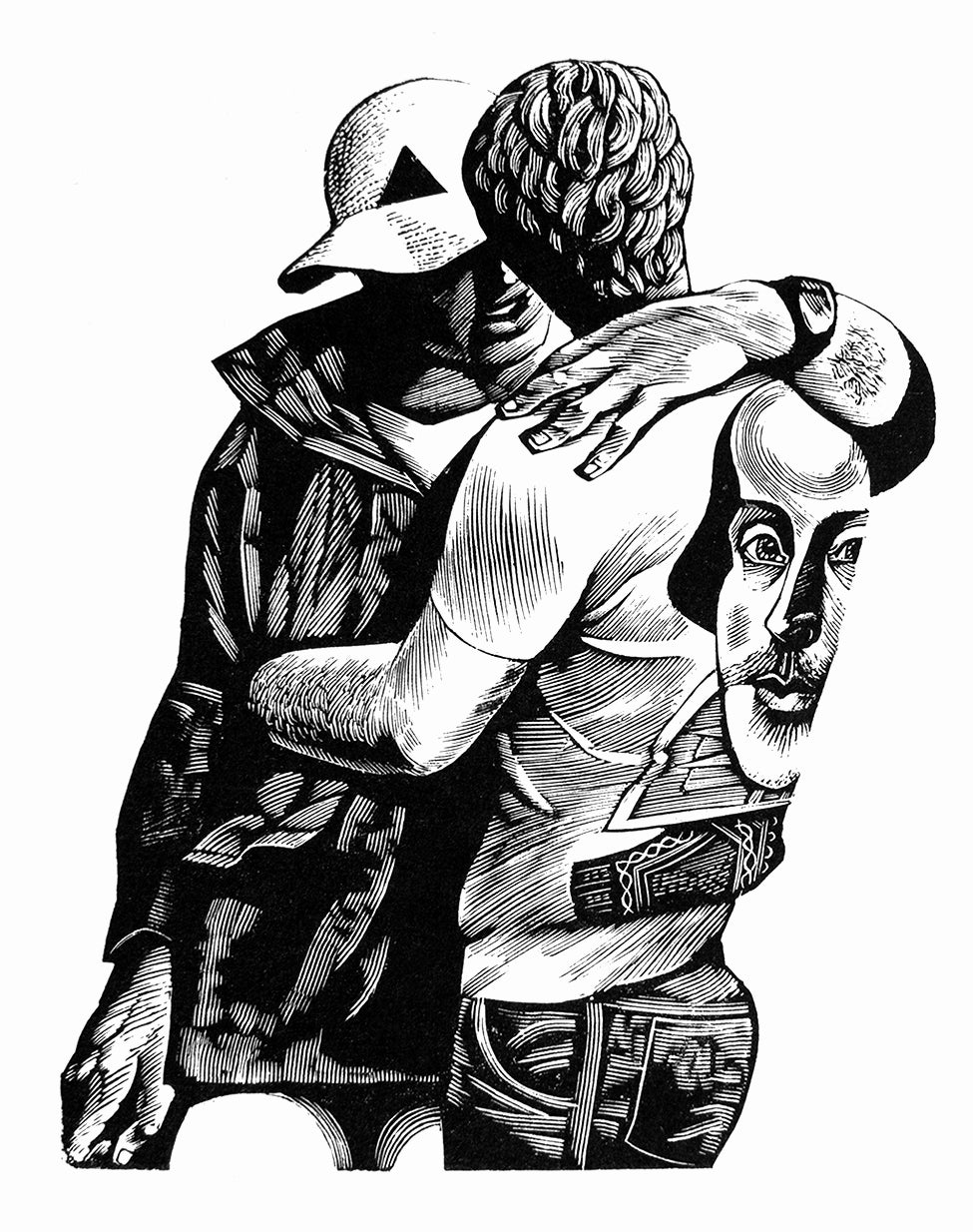

The Shakespeare set was reissued in 1998, with some plays reassigned to different artists. In Peter's case, this included Romeo and Juliet. There is nothing about teenage love in his stark image, just a reminder of the violent family feud at the root of the tragedy. Ever modest and self-critical, Peter never claimed to be a technically expert engraver, but the textures he achieves here, contrasting the harsh foreground with the elegance of the medieval balcony, are highly effective:

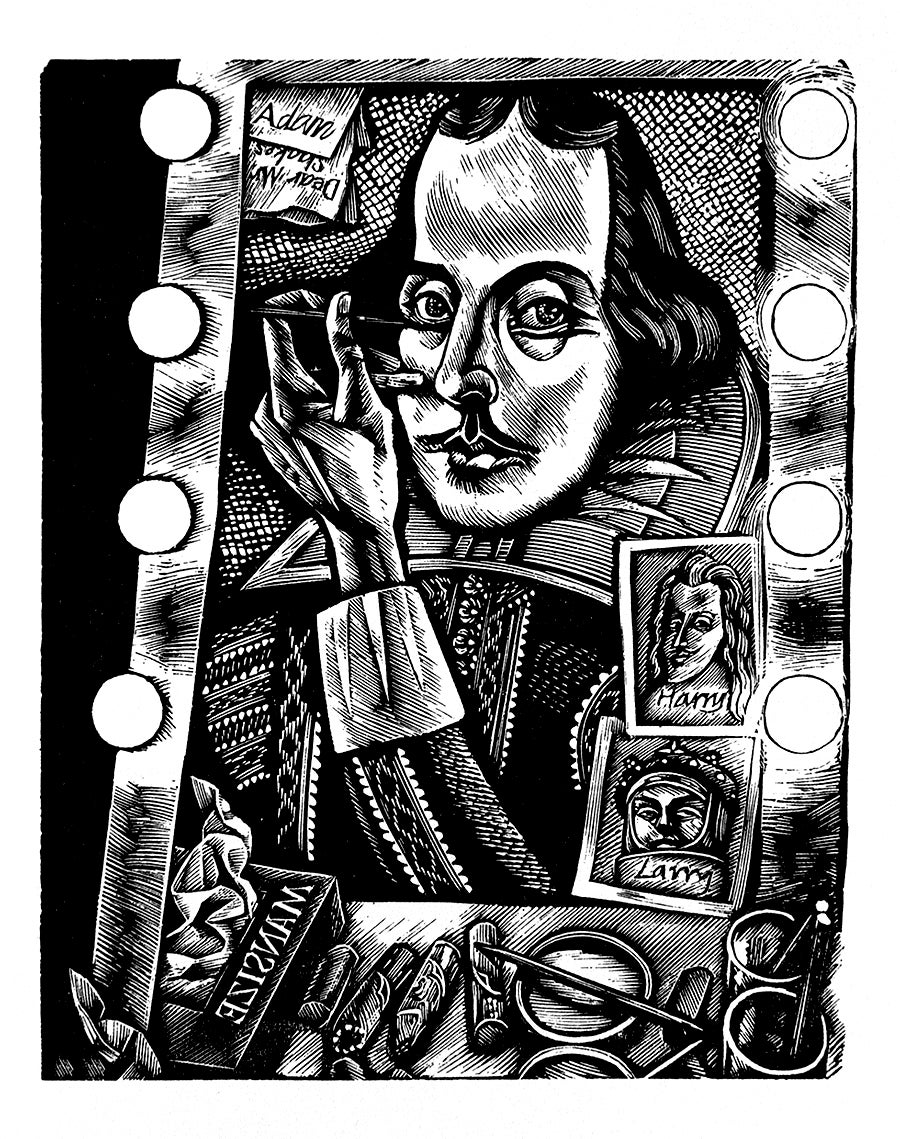

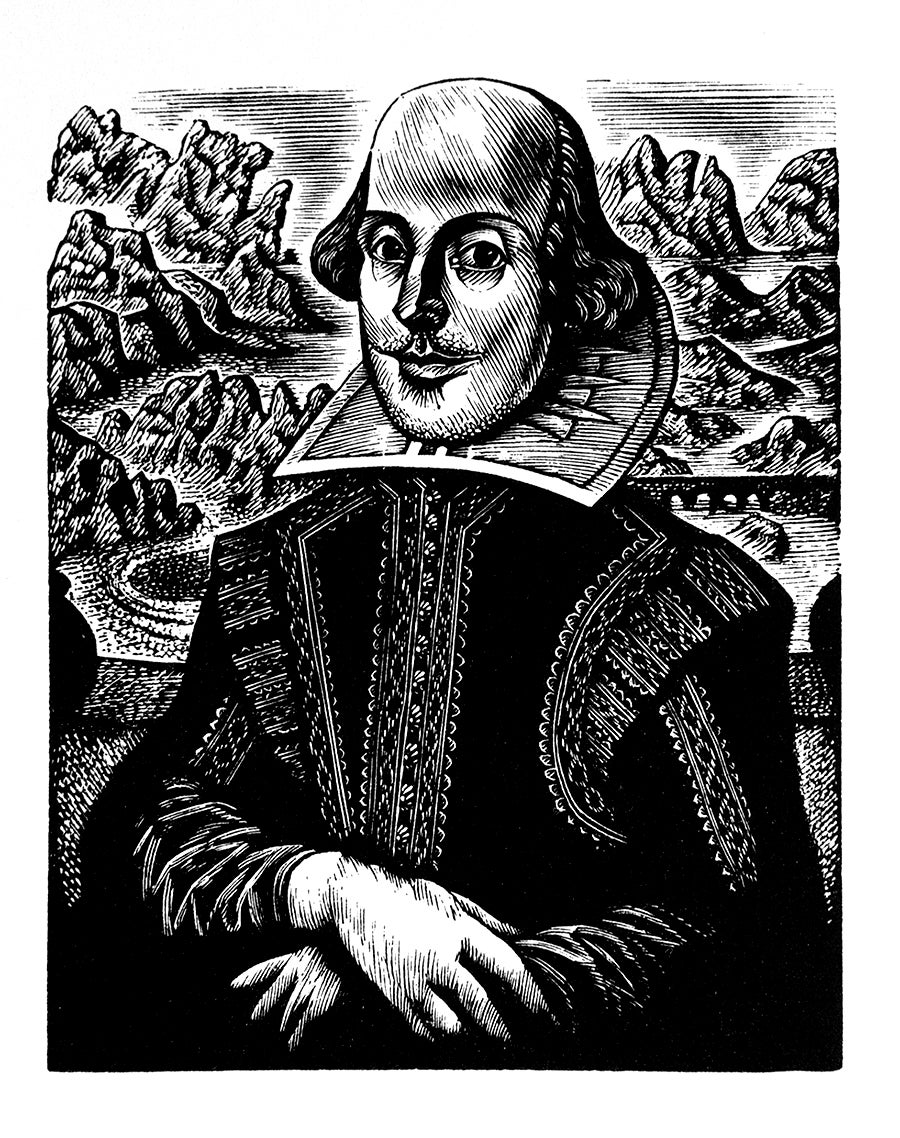

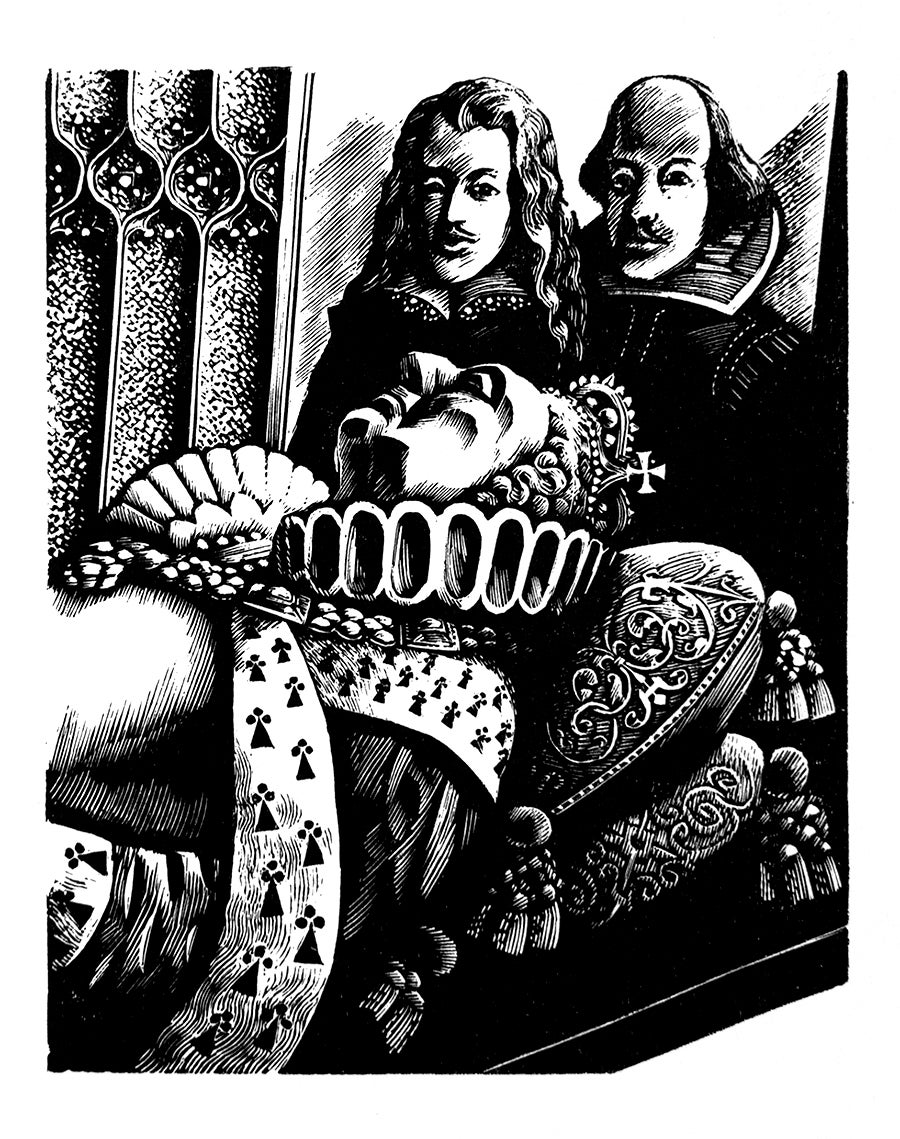

Peter adored Shakespeare, and his next collaborative venture was the Sonnets. Six artists were commissioned to produce six engravings each which would be evenly spaced through the book, and this predetermined the choice of sonnets to be illustrated. This carefully planned approach did not please all the artists, notably Peter, who felt that they should be allowed to choose their own favourites. To prevent bunching or overlaps, some discipline was required, but a system of swaps was worked out, to everyone's ultimate satisfaction. Peter's contributions were all brilliant, and strikingly varied, and are all reproduced here. Shakespeare himself is ever present, and there are guest appearances from Oscar Wilde and the Mona Lisa, amongst others:

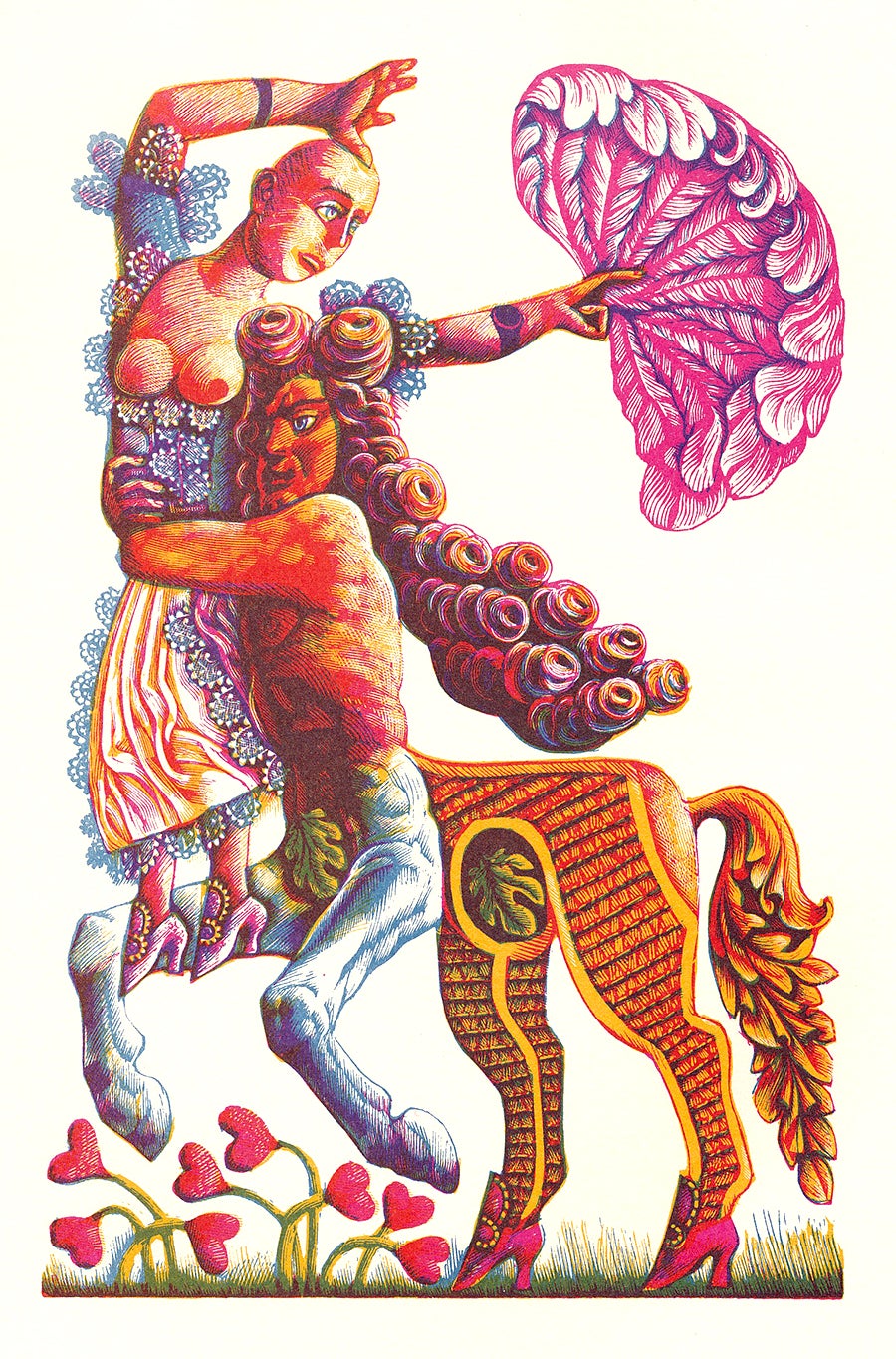

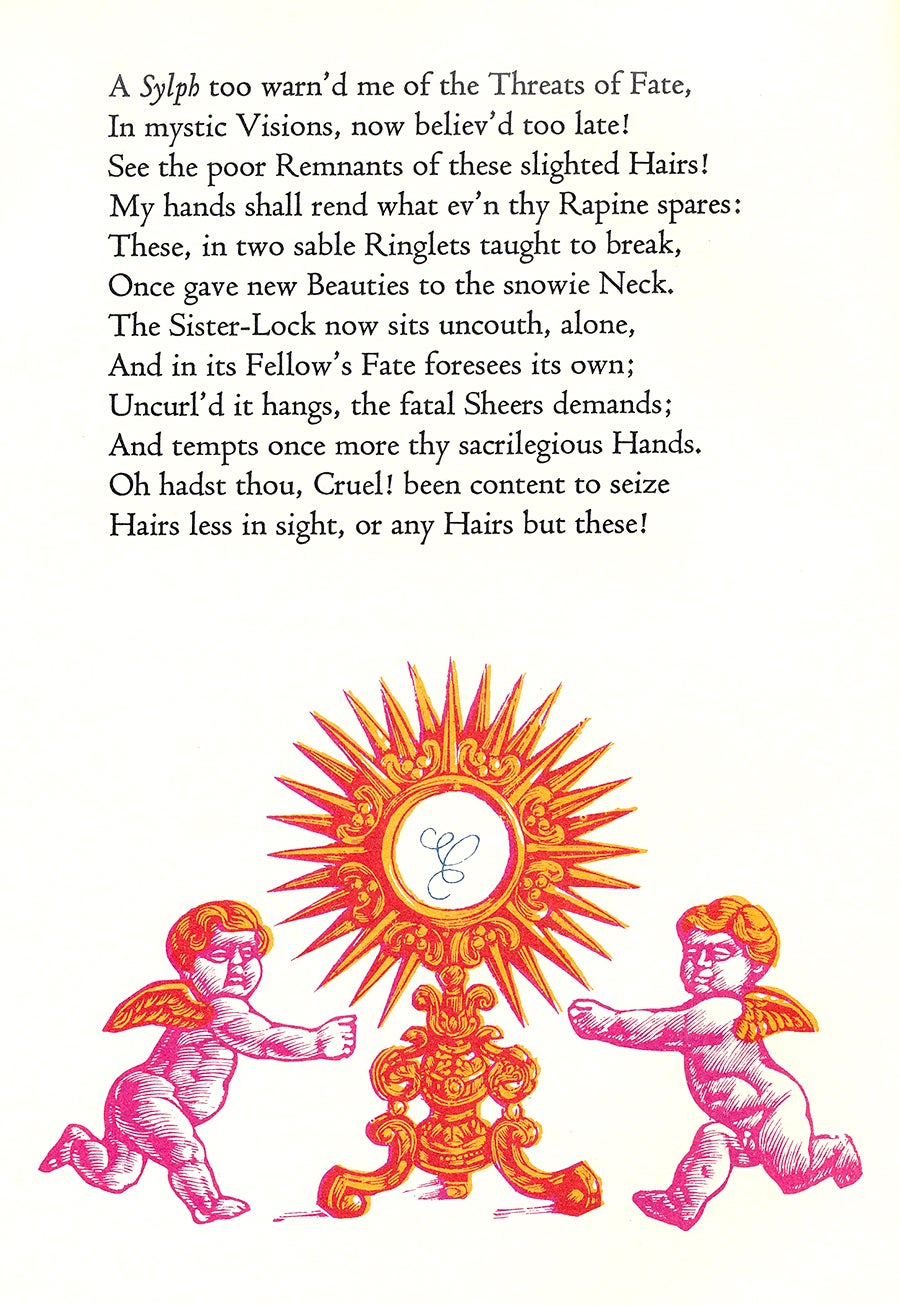

The Folio Press Fine Editions was a series of 20 volumes, published between 1988 and 1991, printed letterpress and illustrated in original print media: mostly either auto-lithographs or wood engravings printed from the blocks. Peter illustrated two of these. As a somewhat spiky character (I don't think he'd mind this description) he was offered a work by that spikiest of poets, Alexander Pope – The Rape of the Lock, his mock-heroic masterpiece. Peter was keen to try his hand at multi-coloured engraving (he was a huge fan of Edwina Ellis, who excels in this medium) which meant cutting three separate blocks for each illustration, overprinted to obtain the intermediate colours. They abound in classical allusion and wig-work, and are fully tuned in to Pope's double-entendres. Here are two of them, the first depicting the villainous Baron wielding his shears, and the second a magnificent centaur absconding with the shorn heroine. Certain anatomical features of centaurs, argued over since antiquity, are solved by the artist in a most satisfying manner.

The book also includes several witty tail pieces. The one below is perhaps the most outrageous of the set (particularly given the lines which precede it). It should be remembered that both Pope and Lord Petre (the original Baron) were Catholics:

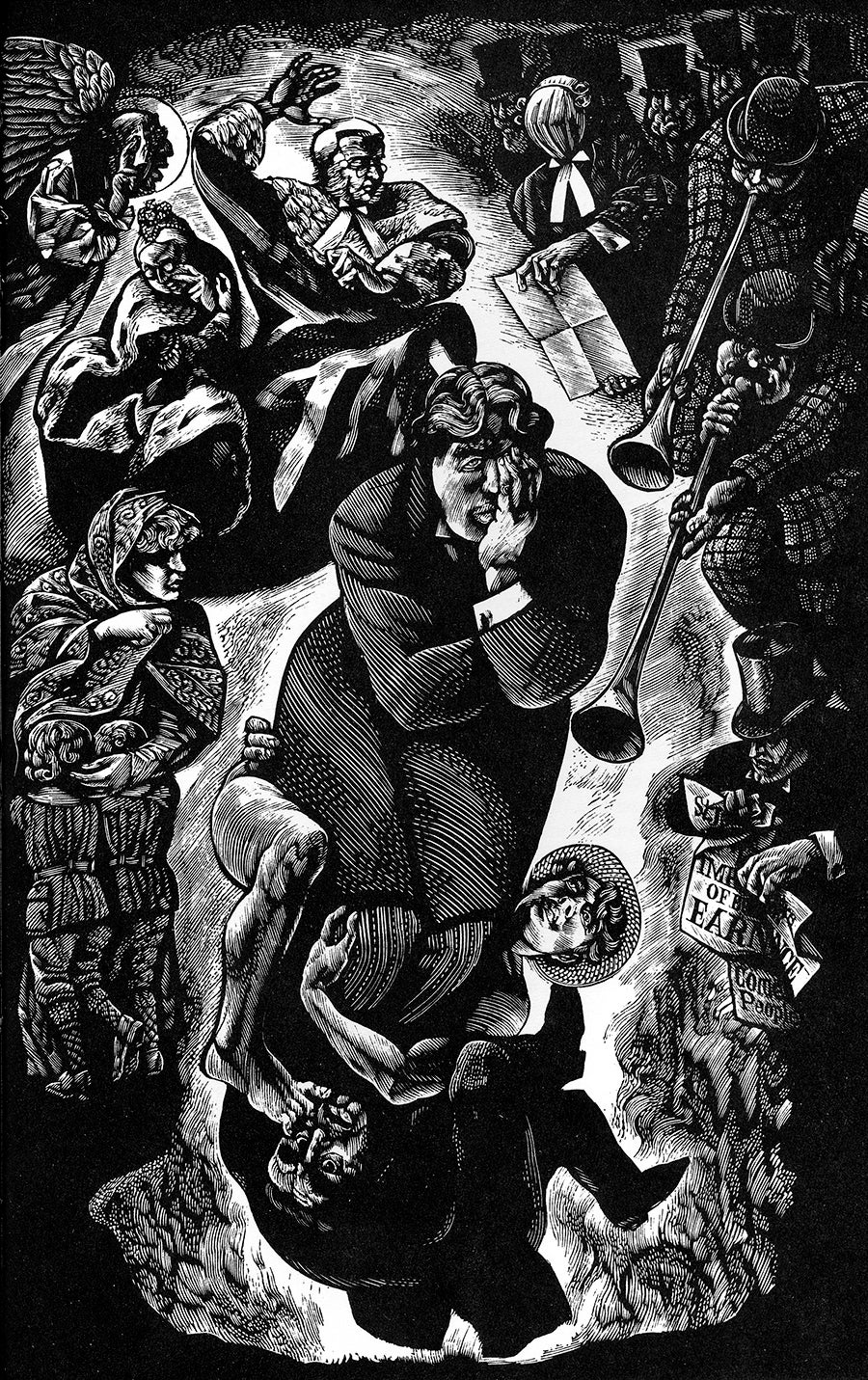

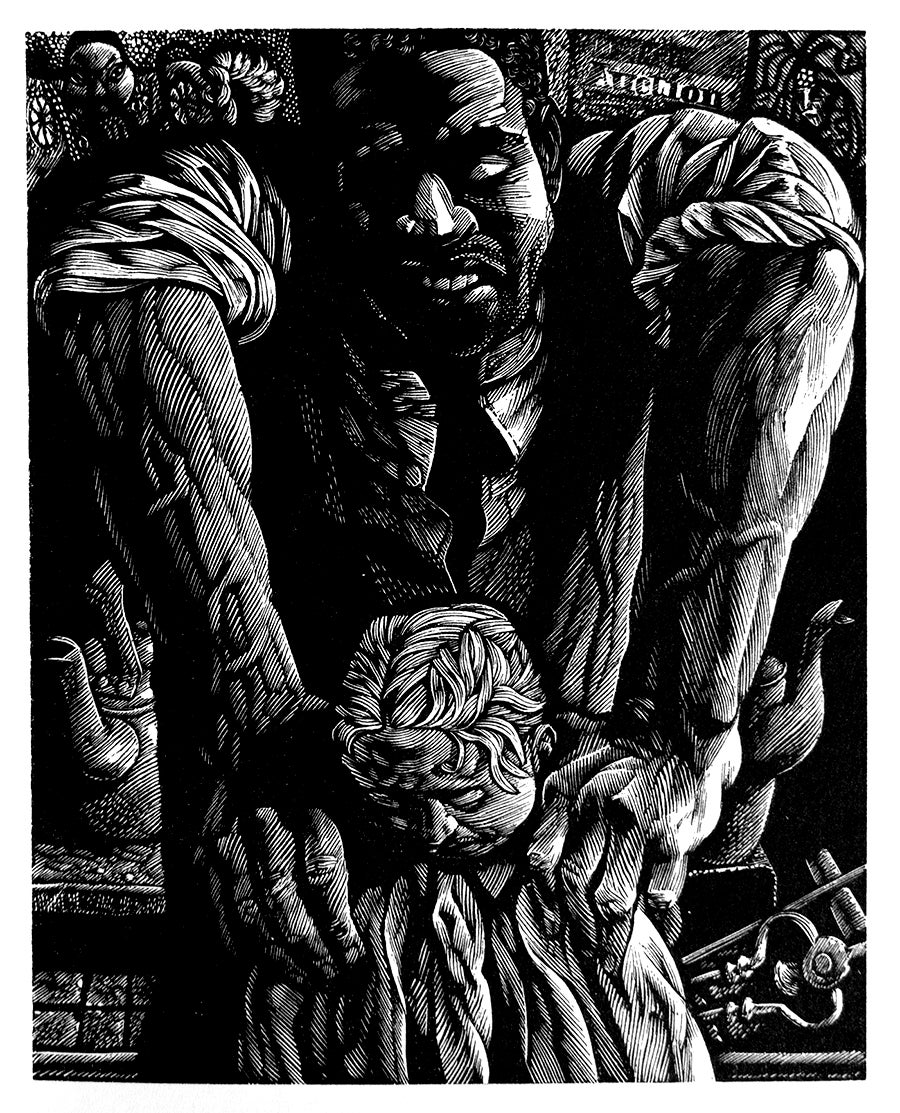

Apart from Shakespeare, the writer about whom Peter felt most passionately was Oscar Wilde, and he proposed to Folio an edition of De Profundis, Wilde's howl of rage and hurt in the form of a letter written in Reading Gaol to his faithless lover Lord Alfred Douglas. With the cooperation of Wilde's grandson Merlin Holland, Peter edited the text as well as illustrating it. These are dark and complex images; the pose of Wilde here is lifted from Michelangelo's Last Judgement, depicting a sinner damned to hell for despair, reminding us of the psalm text which underpins the work:

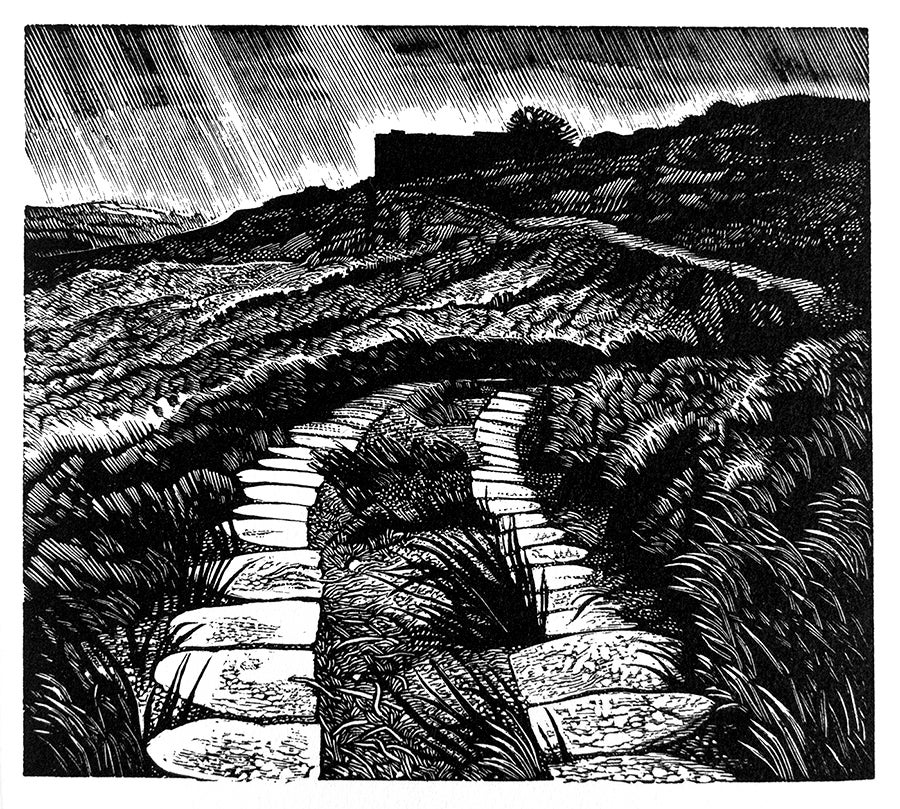

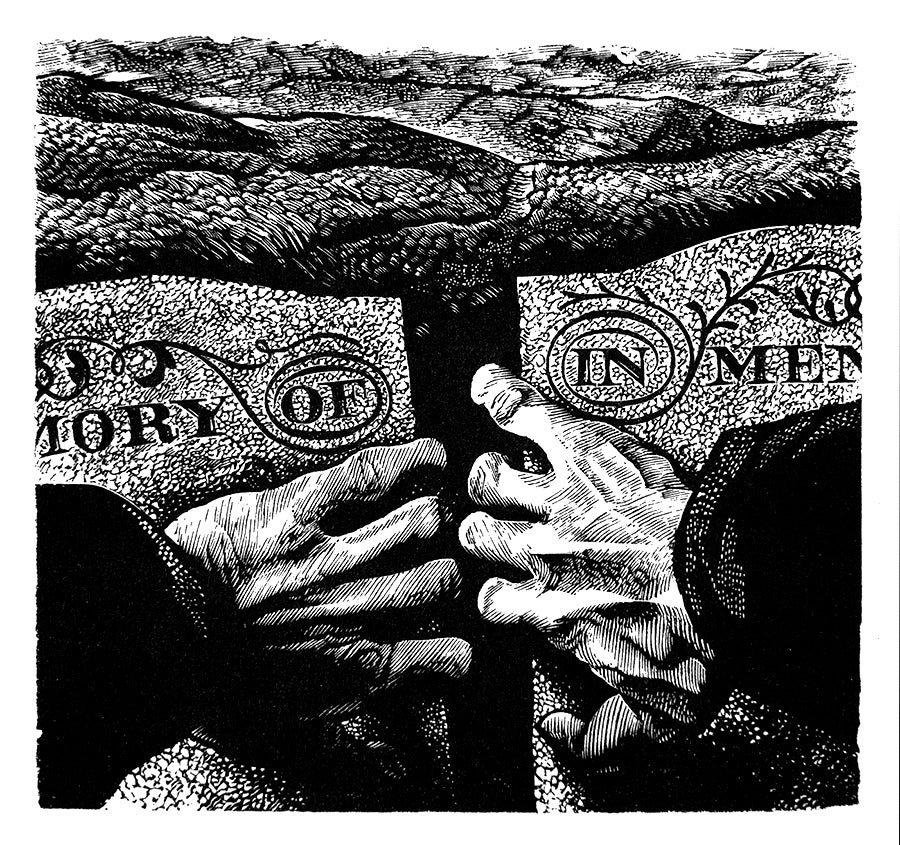

The first novel Peter undertook for Folio was Wuthering Heights, and it is arguably his masterpiece. As will be clear by now, he had no interest in standard 'BBC costume drama' illustrations to the classics. Even what looks to be a fairly conventional moorland scene has a twist to it when we realise that the paving stones are gravestones. The building silhouetted against the skyline is Top Withens, said to be the original Wuthering Heights:

Peter's images are dominated by Heathcliff, an outsider by race and by temperament, with whom he felt a powerful affinity. In this image, Nelly the housekeeper is sprucing up the young Heathcliff, who is ashamed at his appearance when Catherine returns nicely dressed from the Lintons. Nelly describes his eyes as 'that couple of black fiends, so deeply buried, who never open their windows boldly, but lurk glinting under them, like devil's spies.'

And here Heathcliff is reunited with his son Linton – 'God! What a Beauty! . . . Haven't they reared it on snails and sour milk?'

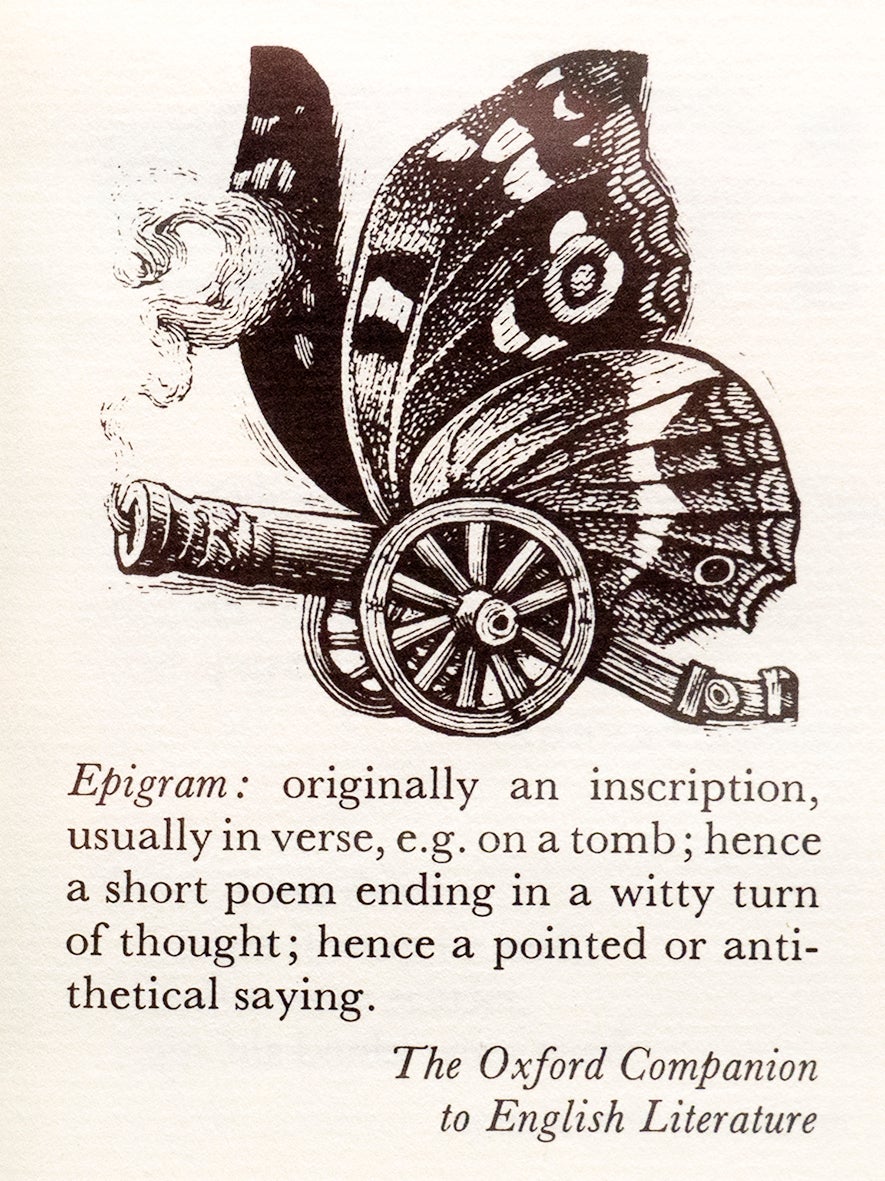

During this period there appeared an annual series of tiny, silk-bound volumes, mainly containing individual poems. An exception was Fifty Epigrams, to which Peter added 18 little images. As can be seen in the pages below, the engravings do not illustrate specific epigrams, but bounce off them, becoming visual epigrams in themselves:

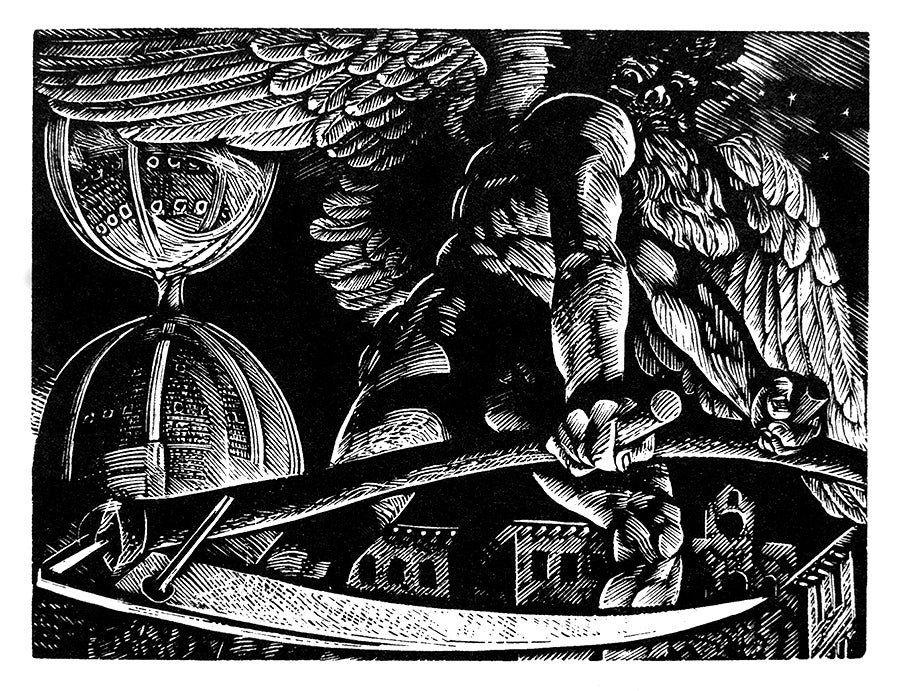

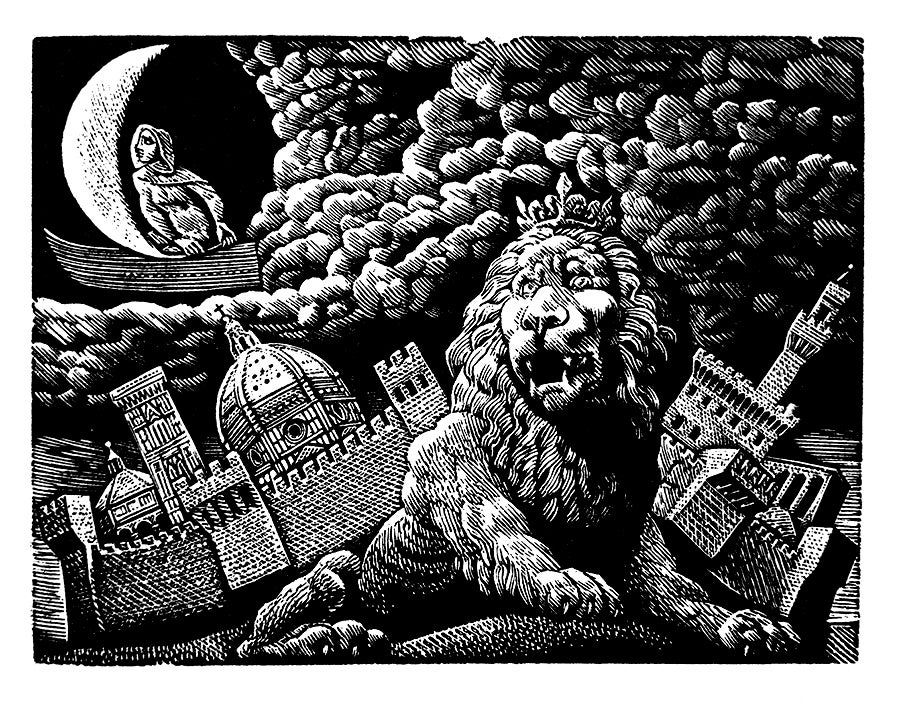

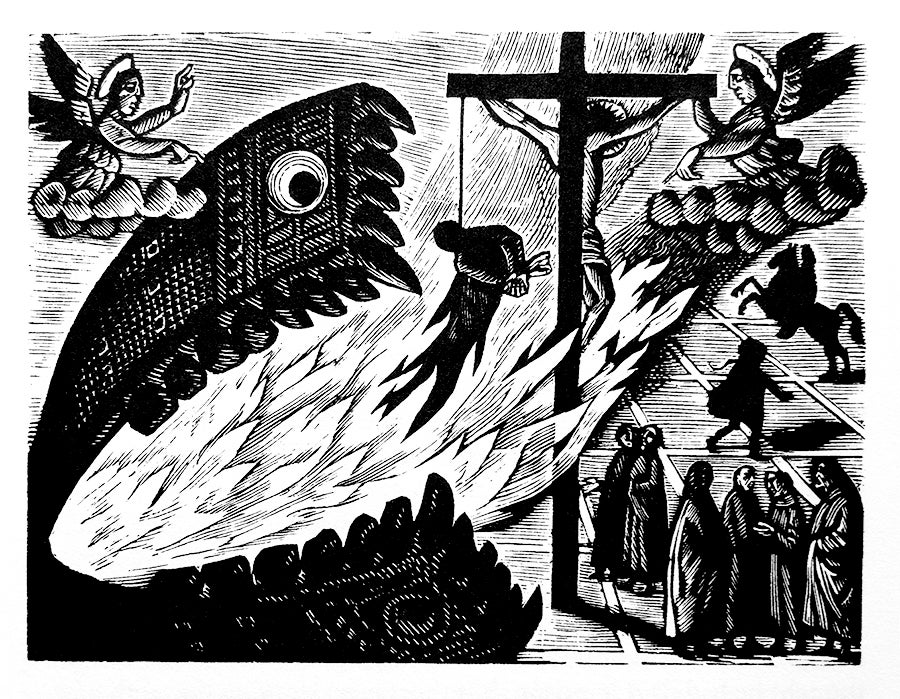

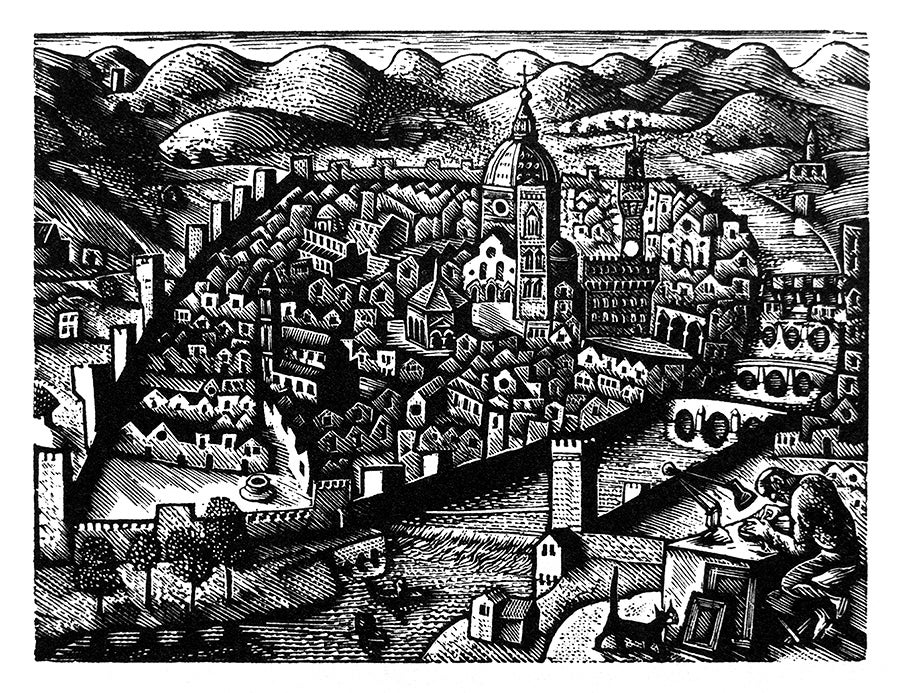

In 1999 Folio published a set of the complete novels of George Eliot, with a different engraver for each. Probably the toughest and least popular of her books is Romola. Peter relished the challenge, immersed himself in the Florentine renaissance, and eventually came to love the book and become its warmest advocate. Each of his 16 engravings incorporates the dome of Florence Cathedral in its design, sometimes artfully concealed:

We finish with a view of the city which could be taken from a 17th-century woodcut – but hang on a moment, who's that, working away in the right-hand corner?

In addition to the books mentioned in this brief survey, Peter illustrated one Folio book with drawings (Nightmare Abbey) and one with collages (The Devil's Dictionary), and designed bindings for two others. These have been excluded for reasons of space, but are well worth tracking down.

Once circumstances permit, it is hoped that a retrospective exhibition of Peter's work will be held, the details of which will be posted as soon as they are known.

Our thanks go to Joe Whitlock Blundell for contributing this blog post. Joe was Production Director of The Folio Society 1986–2015.