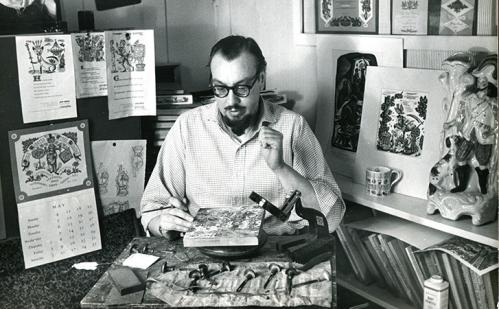

Harry Brockway 1958–2024. PART TWO 2005–21

Joe Whitlock Blundell completes his retrospective look at the Folio Society engravings by Harry Brockway, who died on 1 January 2024.

In part 1 of this blog, we saw Harry's sensitive response to Huckleberry Finn, and in 2005 he returned to Mark Twain for the earlier novel, Tom Sawyer. This book is more of a knockabout tale than Huck; here, for instance, is a scene where Tom collapses with laughter after 'spreading chaos and destruction' around Aunt Polly's house:

But it's not all japes and capers. There is a serious side to the book too, and as ever, Harry is alive to the possibilities for creating powerful compositions. Here the three boys, supposed dead, appear in the church during their own funeral sermon:

And here are Injun Joe and his partner, nodding off, while a terrified Tom looks on, looking for some means of escape:

At that time, Folio was publishing a series of large, handsome volumes, each dedicated to a single poet, and Harry was chosen for WB Yeats. He produced no fewer than seventy-one engravings, and seems to have been thoroughly in tune with the author: perhaps his Welsh blood was particularly sensitive to Yeats's Irishness. The series binding style was quarter-leather with cloth sides printed with a repeat pattern, and Harry's response is masterly, a beautiful entwining of roses with the tower of Ballylee Castle and the wild swans of Coole:

The engravings are very varied. Here for instance is Wandering Aengus and the "glimmering girl/With apple blossom in her hair". It is a mythic dreamworld, stylistically very much of the 1890s, when the poem was written:

By contrast, this image for "The Double Vision of Michael Robartes" employs imagery from Oriental cultures, which so fascinated Yeats:

While this one, showing the sleeping beggar under a pile of stones, is pure Brockway, the figure cramming all the space available:

Harry's talent for portraiture is also in evidence here, for example in these portraits of Lady Gregory and Roger Casement:

Finally the engraving for "Under Ben Bulben", the place where Yeats was finally laid to rest, his gravestone carved with the lines from that poem "Cast a cold eye/On life, on death./Horseman, pass by!"

Having triumphed with Crime and Punishment in 1997, Harry returned to Dostoevsky a decade later for The Brothers Karamazov. Here are the three brothers, all strongly characterised:

One dramatic scene follows another. Here is Captain Snegiryov showing his contempt for the hush-money he has been offered by trampling it into the ground (though he later accepts the money!):

Equally dramatic, in a different way, is the scene where Mitya is hiding outside the window of the father he detests, and the old man sticks his head out: "his pendulous Adam's apple, his hooked nose, his lips, twisted in a lurid smile of expectation, were all brightly lighted up by the slanting light of the lamp…"

Finally, we see Mitya at Dimitri's trial, "his hands tightly clasped, is teeth clenched and his eyes fixed on the ground," while the twelve jurymen look on impassively. As so often, Harry expresses much through his depiction of hands:

Harry was next asked to engrave the illustrations for a super deluxe edition of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Other Poems by Coleridge. For the first time, he was asked to hand-colour the prints before they were reproduced. Here are three examples, one each from the Rime, Christabel and Kubla Khan. Each plate was tipped onto the page within a border designed by Harry, elements of which appear in all the illustrations:

Harry himself never felt totally comfortable with the colouring idea, and he later editioned the prints it was omitted. And it is true that the most powerful image in the book, the frontispiece (which was handprinted by the superb pressman Ian Mortimer) is in black only:

Folio presented Harry with one poetic challenge after another, none more so than The Vision of Piers Plowman, the magnificent – but very long and intellectually tough – mediaeval masterpiece. The poem is formed of a prologue and twenty cantos (called "Passus") and Harry cut an engraving for each of them. It was published in parallel text, and to make the lines balance, each engraving was paired with another one, giving the number of the Passus.

We start with the Prologue, a delightful image illustrating the Council of "a rabble of rats… And little mice along with them, no less than a thousand," which is invaded by a troublesome cat:

The poem is rich with allegorical visions, each of which the artist had to get his head round (and it's not easy!) before he could illustrate them. Here in Passus 5 Piers meets a magnificently clad professional pilgrim:

Passus 11 contains a dream-within-a-dream, in which our hero is tempted by "Lust of the flesh":

The image for Passus 20 is particularly spectacular: the Antichrist, having cut the branches of the tree of Truth, then turns the tree upside down, tearing up the roots:

But my favourite of all is the frontispiece, which we will come to later.

In a startling change of direction, Harry then was asked to illustrate a set of crime novels featuring George Simenon's Inspector Maigret. Six volumes were published in all, each with four illustrations within the text and a larger frontispiece. Here is the frontispiece to Maigret sets a Trap, featuring splendid hat-work:

Descriptions of the weather are an important feature of setting the atmosphere in each of the Maigret books, and Harry frequently picks up on this:

His method is cinematic, with wide-angle 'shots' alternating with close-ups:

And it's good to see the largely unsung heroine, Madame Maigret, making a cameo appearance:

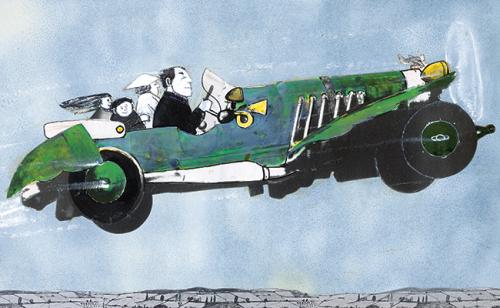

Another stylistic swerve was required for his next commission, Brideshead Revisited, in which he conjures up the world of the 1930s in a series of two-colour plates. Some of these are clearly inspired by travel posters from the period:

Quite a different mood is conjured for Lord Marchmain's deathbed scene, the baroque excesses of his four-poster bed imagined with great relish:

Harry returned to Dostoevsky for what proved to be his last Folio commission, a selection of The Best Short Stories. These engravings seem to me more directly influenced by Russian art than his earlier Dostoevsky images, notably in "The Christmas Tree and a Wedding" (what a creepy image!):

However, the engraving for "The Peasant Marey" harks back to the world of Piers Plowman:

And it is with Piers Plowman that I'd like to finish, the frontispiece mentioned earlier, which also depicts a sleeping man. This man – Piers himself, the author William Langland, or the artist (or all three) – is a visionary, conjuring up in his imagination an entire world of characters, the men and women who populate the poem. In just such a way has Harry Brockway imagined entire worlds to enrich our enjoyment of the world's great literature, from Shakespeare to Yeats, Anne Bronte to Mark Twain. And crowning the scene, appropriately enough, is the Tor at Glastonbury, Harry's home for so much of his life: